@Johannes Kepler University (JKU), Linz: Motivated mainly by the apparent connection between AI technologies and approaches like modeling and NLP/LLM (Natural Language Processing/Large Language Models) and my discipline, ECM - with some teaching/mentoring mixed in too.

academic blog post overview

Masters thesis project, and here a blog-post synthesis of the main LLM/ML work upshot of the thesis itself

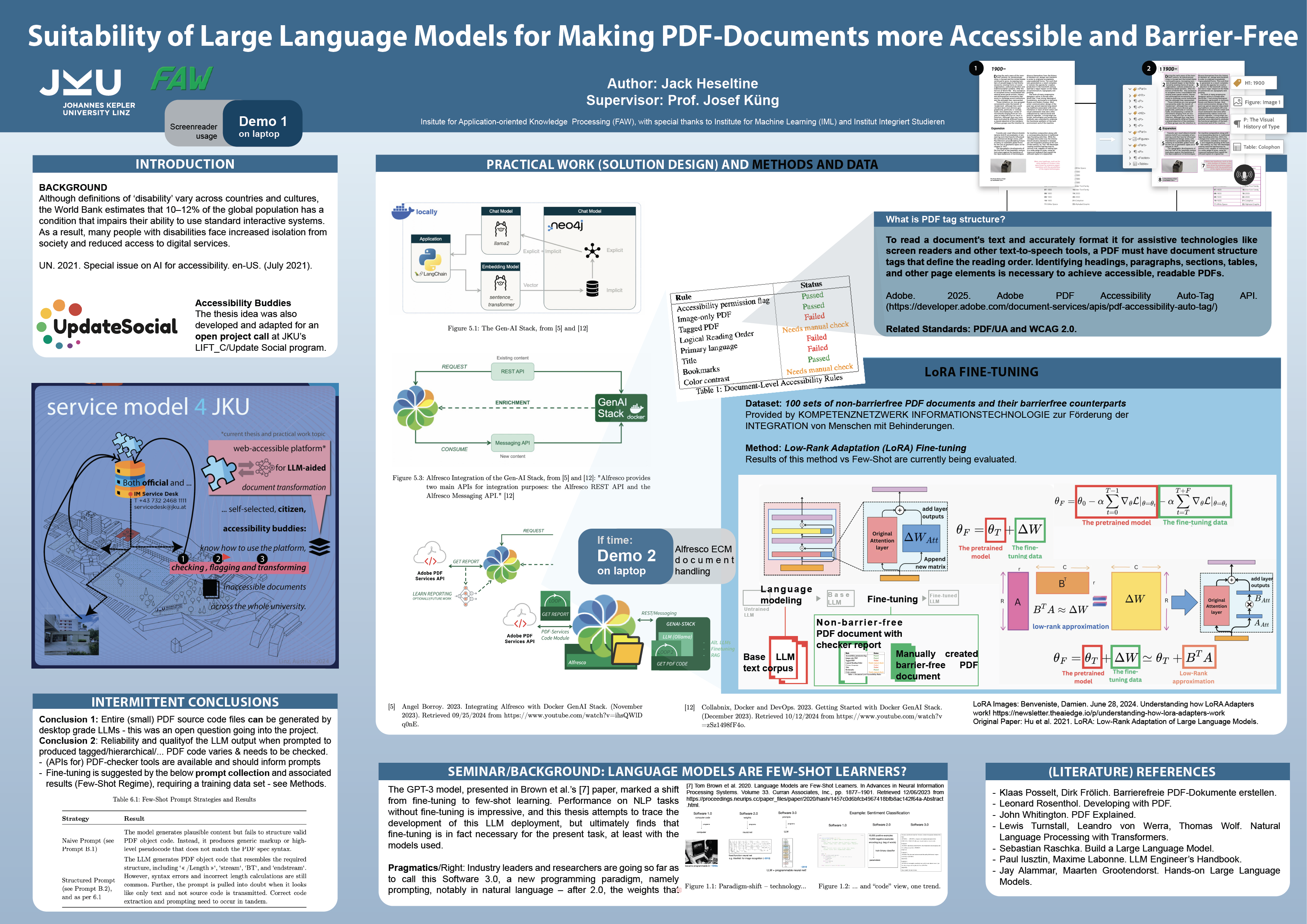

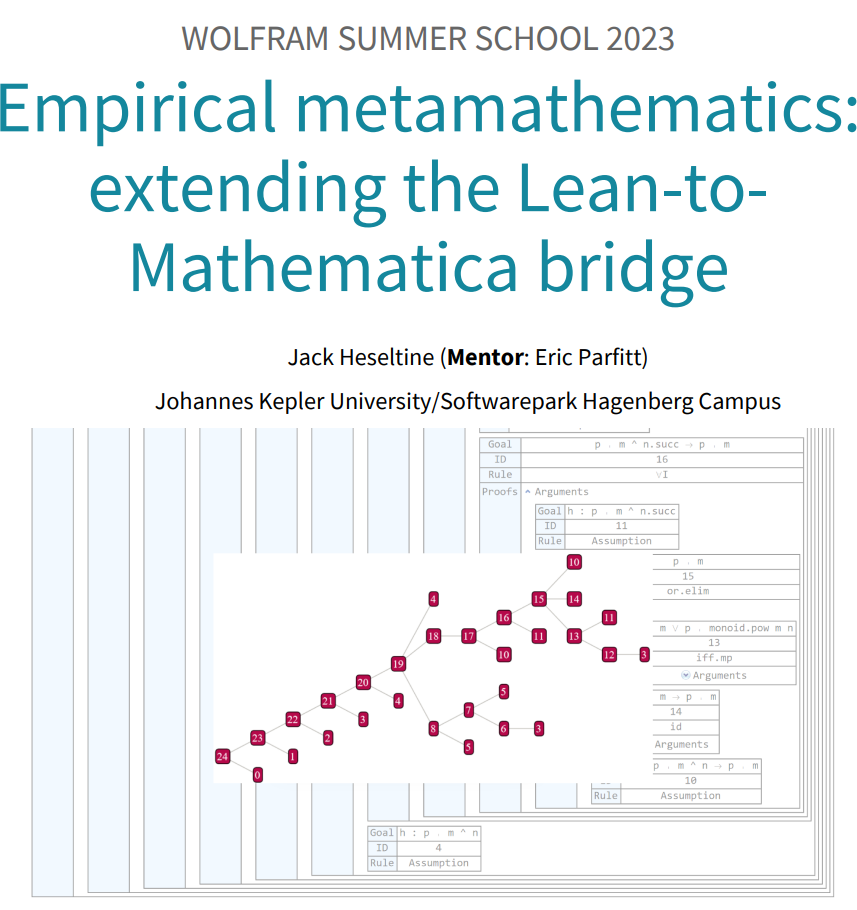

Poster, as linked in my portfolio (practical part), for a quick overview:

-

Knowledge Graph from Text, or Explainability for Understanding Argumentation (Project)

In this Masters-level Group Project I took on the role of planning an XAI (Explainable AI) experiment set to match an exciting paper in dealing with Argumentation Graph Construction, aiming to make headway in our understanding of the interplay of text and graph under a given model-assumption.

-

Reinforcement Learning Goes Deep (Part II)

Reinforcement Learning Goes Deep (Part II)Part II covers Deep Q-Network (DQN) for MiniGrid, with a recap of the relevant basics, and challenge code.

Part I: Q-learning Algorithm Implementation for a Grid World Environment

-

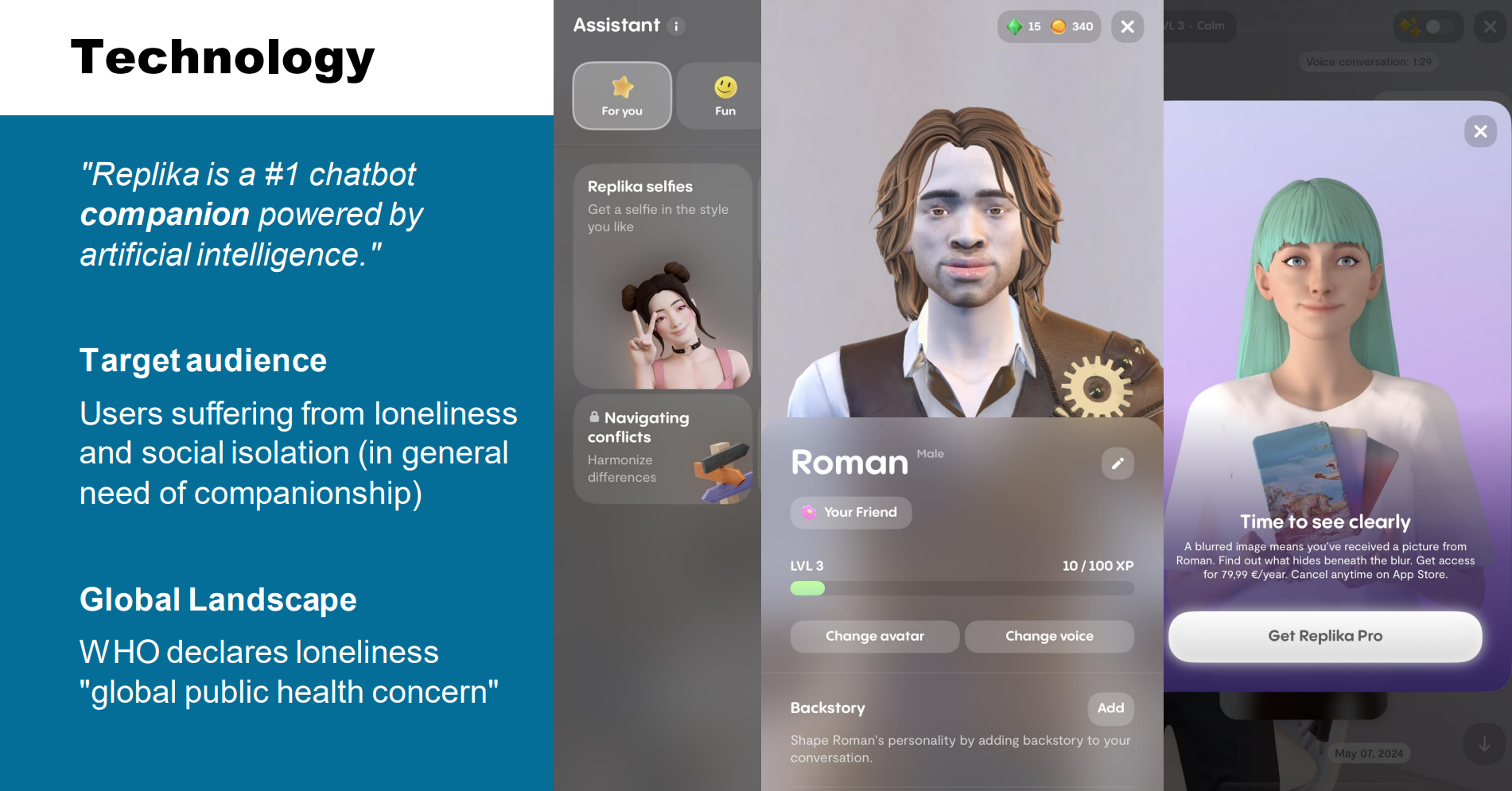

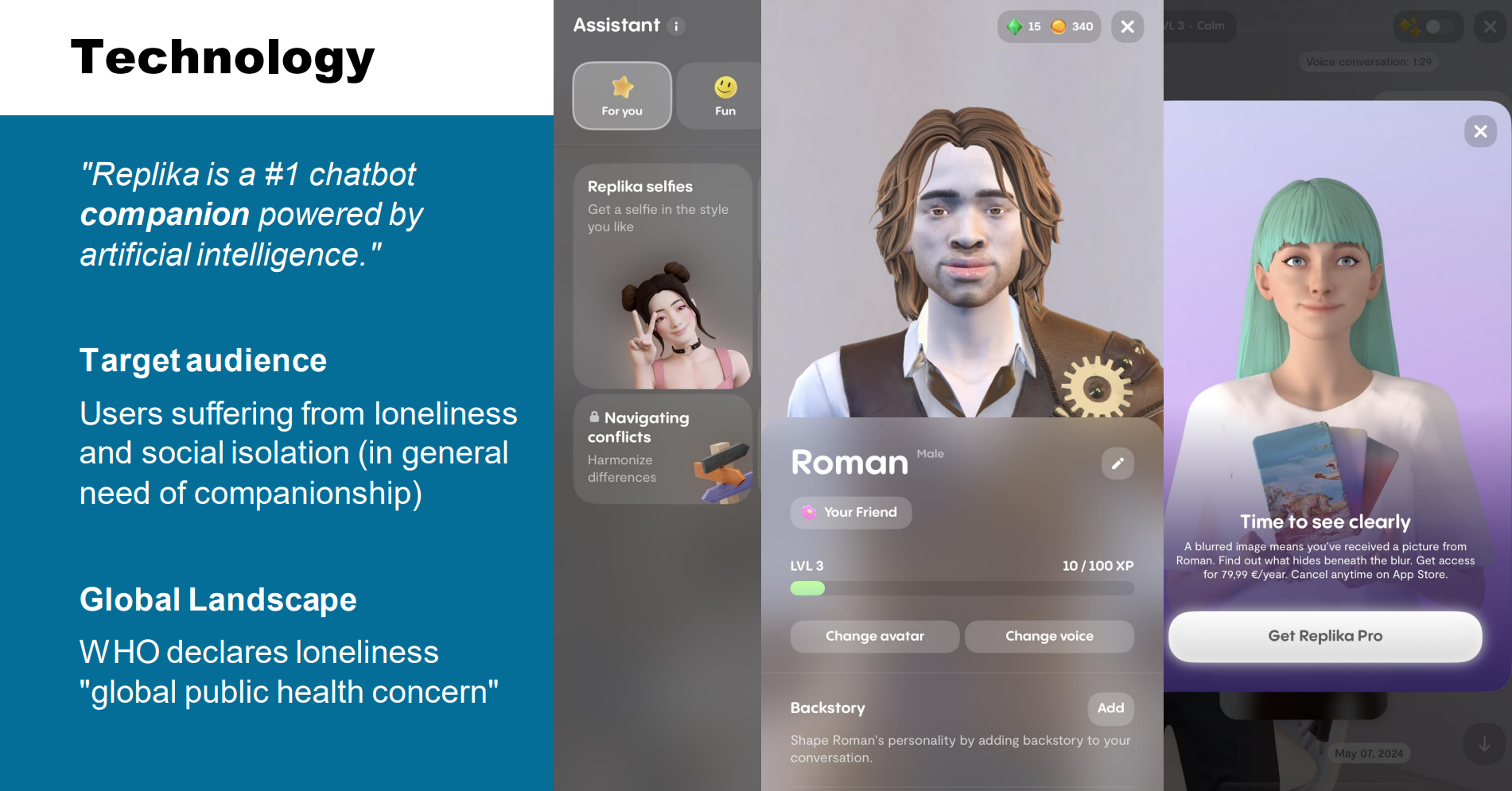

Presentation: Replika

Course-presentation about the AI companion app in its current iteration. Includes use case study with persona and AI product improvement.

-

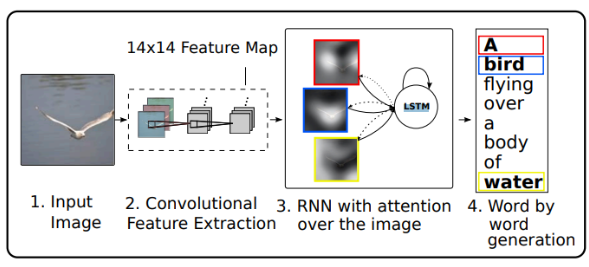

Attention via LSTM, the Transformer-Connection

LSTM's Temporal Attention as the way into this topic: why process all input, when only some parts are relevant? I want to end on the simplifications Transformers make, while focusing on Attention for seq2seq, i.e. Sequence-to-Sequence models.

(End-of-story? We'll see, maybe in Linz!)

-

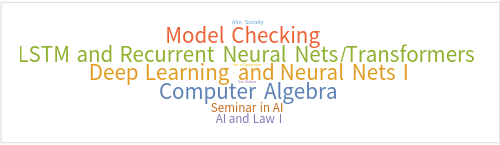

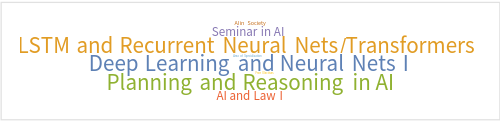

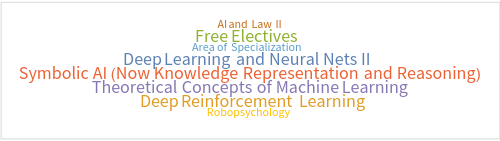

LSTM in the Linz AI Curriculum

Includes some WL (Wolfram Language). (Let's always include some WL.) My focus here is on LSTM for language (seq2seq and generative), but I build up from the basics and draw on the most helpful resources I could find where needed, though still following the central JKU AI course's presentation of the topic.

-

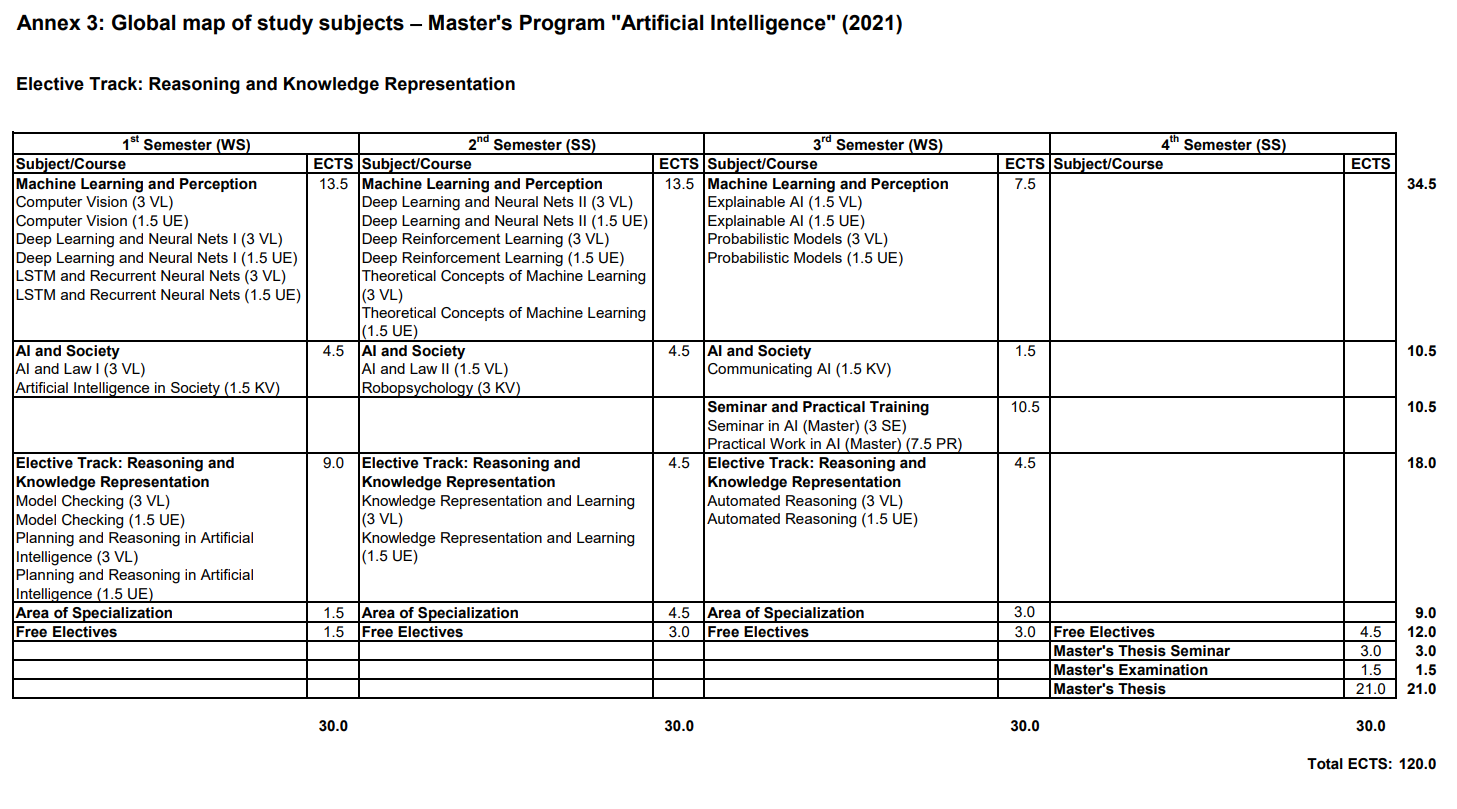

Presentation: Language Models are Few-Shot Learners

Seminar-presentation/Thesis I. Next up a practical component and the thesis itself.

Some housekeeping notes on my degree, and shorter tool-oriented posts about Wolfram Language, Prolog (!), and SMT2 for model checking and for planning are also here, whereas further Wolfram Language work is documented as part of my engagement at Wolfram Research.

rX Feed (really, notes on how to apply this stuff) and my formal thesis in its different parts, interlaced with these blog posts, become part of the same project, I find: I hope you have fun reading! All credit for the techniques presented goes to the authors. All errors in their presentation are mine. I am happy for you to get in touch for any comments, suggestions and any notes you have for me about the material.

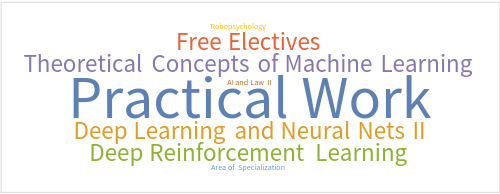

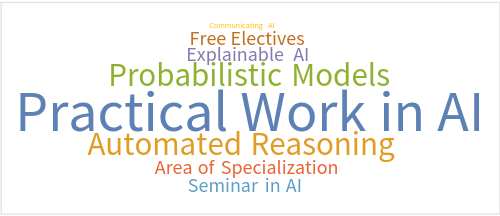

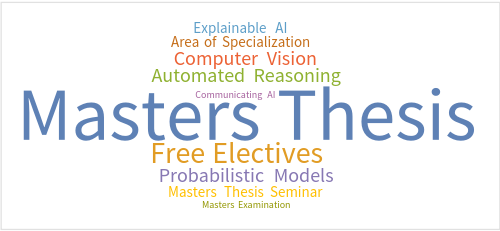

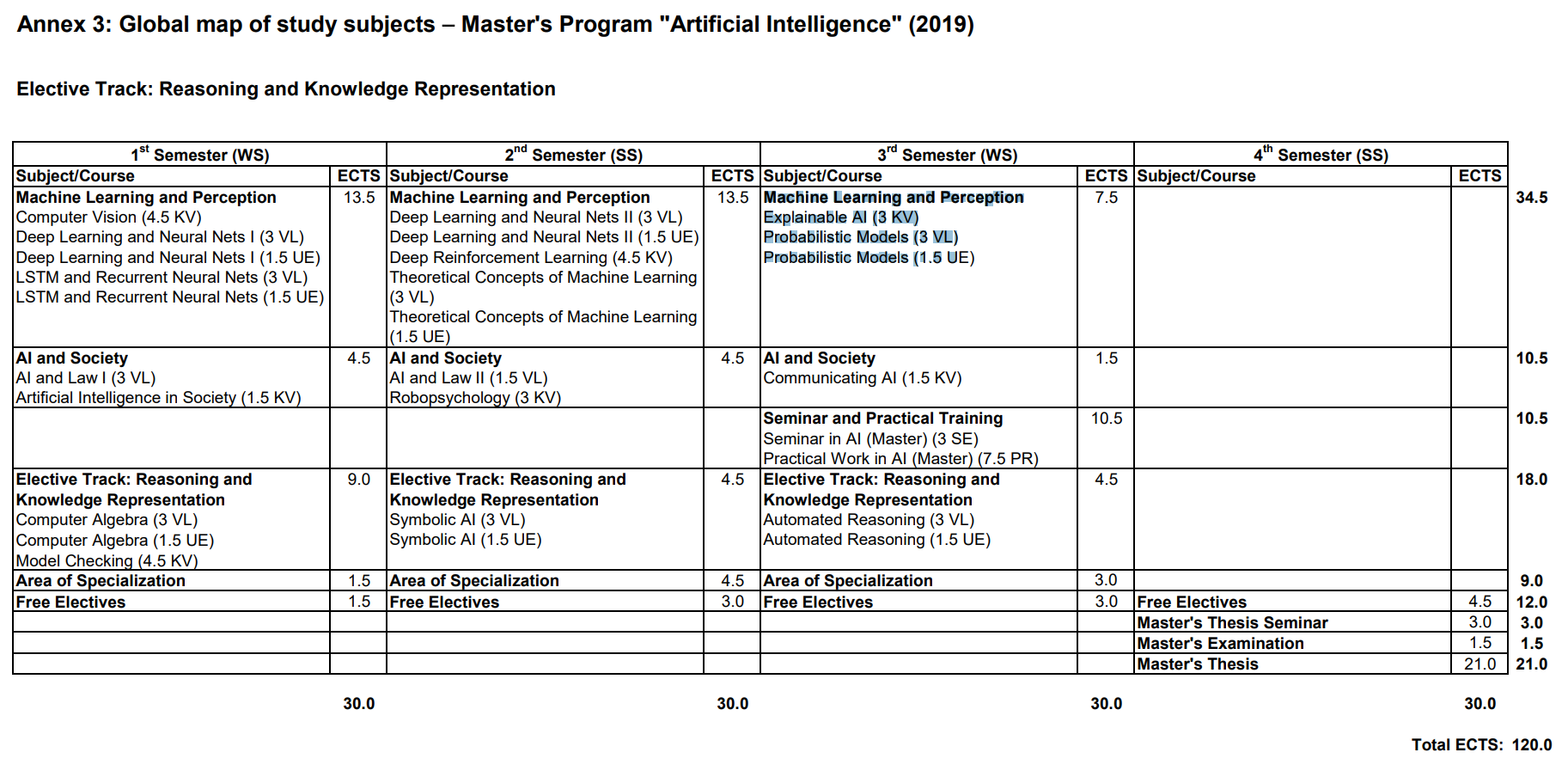

These Masters level studies are on-going (target December 2024), now full-time, and occurring in the context of the Symbolic/Mathematical Track @JKU's AI Masters in AI. The most up-to-date curriculum is listed in English and I also wrote a concept document for a potential Symbolic Computation direction of these studies post-Masters here in Linz, where however LLMs and their application too are taking center-stage for now, as my Masters contribution to the Zeitgeist.

IT:U - LLM Benchmarking (PhD Interview)

See also XAI Project.

The following is a set of presentations and their notes, especially, delivered as part of interviewing for the new IT-U NLP Group Computational X PhD program in Linz. I am motivated to study in this group due to on-going touchpoints in my studies with NLP, and of course the real industry-relevance of current trends in LLMs particularly, but will use the following interview format to unpack how I got here.

This presentation/conversation is structured as follows (main content, highlighted, below).

- intro Prof.: 3 mins

- intro self (academic), see below: 5 mins

- general Q&A: 12 mins

- presentation own work, see below: 15 mins incl. Q&A

- presentation NLP Group work (Holmes paper), see below: 12 mins plus 8 mins Q&A

- own questions (see below!): 5 mins

Personal Introduction (Academic)

in 5 mins

The main points: I am an …

- engineer (at the time of IT:U entry full BScEng-level formal training in Software Engineering from Hagenberg) with research (completing my Masters in AI, see degree plan with curricula on this page), Wolfram Research angle

- expressions (symbolic idea) vs NLP (*)

- interdisciplinary, Liberal Arts background: connection to NLP definition below

- member of IT:U Founding Lab (2023) and the 2024 summer school, understanding the overall IT:U spirit and origin

- broader, seminar-based initial undergrad in the US focussed on writing and independent research, which I credit with being able to shape my own academic route and define my own research questions and projects since, as documented on this blog for instance, and also, a spirit similar to the one I am finding at IT:U (interdisciplinary projects, seminars over lectures, etc. - more high-tech however)

- My current (Masters) thesis is an LLM application/evaluation topic, making PDFs barrierfree and accessible: see the next section, connection to IT:U NLP Lab's goals

- I have my own vision for IT:U too: see Linz context down below, and emphasizing both interational, academic perspective and the potentially more business-driven, local (roots) view.

- My personal vision: (see also academic resume for) a professionally oriented vision, With the upcoming wolfram.ai and LLM Assistant products, Mathematica is being supplied with RAG-guided LLM capabilities. The (PhD/+ level) researchers on the project host a Software-oriented discussion circle I actively participate in: my ambition for my PhD work is to unlock similar professional frontiers, at Wolfram Research or elsewhere.

A (*) definition from the IT:U website, stressing the interdisciplinary aspect: multidisciplinary research field within artificial intelligence (AI) that integrates principles from computer science, linguistics, cognitive science, and related disciplines. It aims to enable machines to understand, interpret, and generate human language across various societal domains, including education, healthcare, scientific research, finance, and beyond. (From the IT:U NLP Group page)

In this context:

IT:U NLP goals, within the application areas outlined above:

- (a) to develop robust and trustworthy language processing techniques informed by linguistic principles for understanding and generating human language

- (b) to build human-centered NLP applications that advance education, social sciences, humanities, and scientific discovery (From the IT:U NLP Group page)

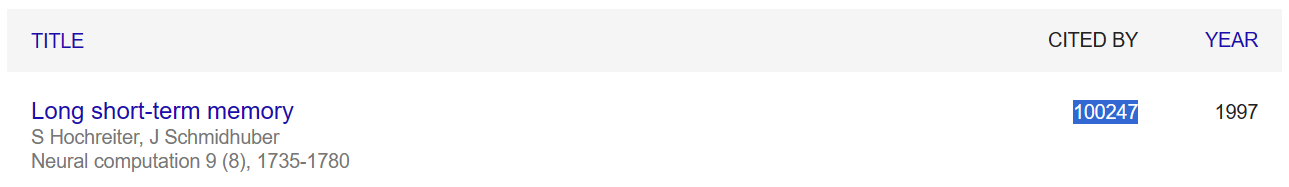

I am noting the focus on developing (techniques) and building (applications) in the above and so would add the Linz-specfic context as well, that of JKU IML (Institute of Machine Learning) under Hochreiter and the current development around xLSTM with a turn to applications in the form of NXAI at Tabakfabrik, and the vibrant IT ecosystem in Linz and Upper Austria overall - these contexts inform my application to IT:U in this field, where I would consider an NLP-applications oriented NXAI collaboration an important potential.

Side: Even more, I believe that the studies that happen inside IT:U's groups at the inception moment of the university are so crucial to what this university is to become for this city: here I also want to mention my postit:u effort, most recently collecting statements from mayoral candidates about IT:U's status as it looks for a site, and particularly PostCity as a viable option: the consensus about the suitability of the site is astounding and I am going to stay on top of the project regardless of the outcome of this application to follow the political discourse on the subject vice versa business interests that seem to drive ecologically devastating alternative approaches, such as the abandoned proposal to use greenland for the university. In this way I see a real political relevance of what happens at IT:U, and what I want do at IT:U also. Project outcome for now: (pre-election) mayoral candidate statement collection (for accountability) and the IT:U Linz Location Story from the perspective of Founding Lab and students at JKU/KHJ, keeping the narrative in check and making the developments visible to outsiders, especially in an election context (January 12th Linz Mayoral Election).

On the topic of relevance, I am particularly excited about IT:U's NLP Group's applications-oriented PhD-offering, which I prefer to JKU's current one in AI* because of this orientation exactly. I think more global developments at IT:U like the Industry Sounding Board can help set this university apart, noting a potential challenge of academic freedom vs. drive towards applications, which I would answer with the whole network university idea, i.e. being a hub for a collective of spinoffs.

*JKU is offering some "Symbolic AI" topics with the current Bilateral AI PhD Cluster of Excellence, which is interesting to me from an academic perspective, and I will most likely apply as backup as well, but finding the way into practical relevance is actually a priority for me, truly.

So to complete this section I would connect to goals (a) and (b) from my current thesis topic and my professional background respectively.

My hope is that learnings from the research going into these presentations, as well as the discussions at interview, will inform the thesis itself, adding a perspective, especially on the question of (task-specific) evaluation/benchmarking of LLM performance.

Own Work: PDF Accessibilty, Approaching the Benchmarking Question (Hoffman)

in 15 mins incl. Q&A

IT:U Work: LLM Benchmarking (Holmes)

in 15 mins plus Q&A (8 mins)

FlashHOLMES take-home exercise exercise suggestion

I have not had the time yet to apply FlashHOLMES, which I would be intrigued to try, and can offer this as further work in early Febrary or later (due to the exam season now in January) if this is helpful, depending on how applications are further processed and as a potential take-home exercise I would be excited about.

Research Agenda (probably best for Q&A)

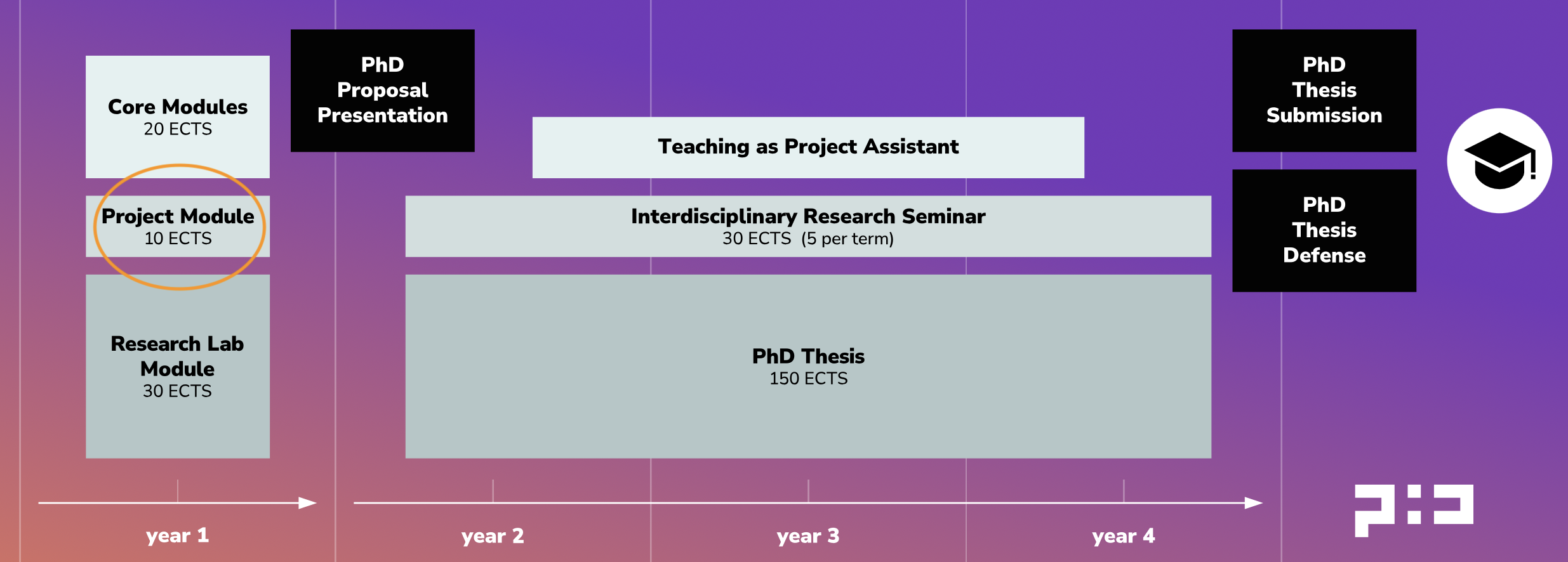

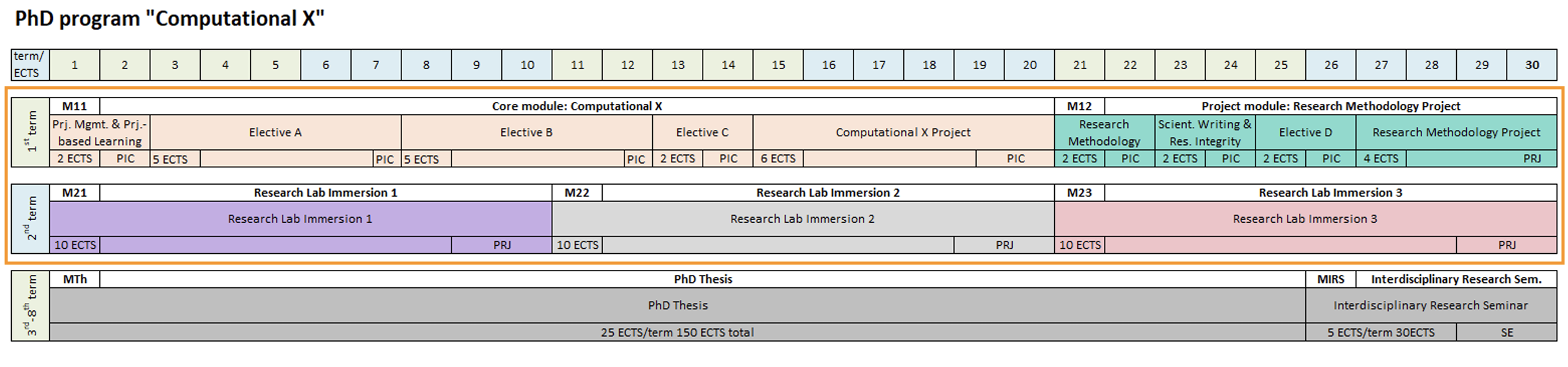

I think it helfpul to pin this on the year 1 Project Module (Computational X Project and/or Research Methodology Project, see also below and in the curriculum):

From the curriculum:

This course [Research Methodology Project] provides a practical introduction to the methods and techniques of academic research. Students will learn about research design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Through a real-world project, students will apply theoretical knowledge to develop research questions, conduct literature reviews, and implement research methods. The course emphasizes critical thinking, analytical skills, and collaboration, equipping students with the tools and experience necessary to conduct effective and ethical research in an interdisciplinary context.

For this, I would very much like to segue directly from the research and validation orientation of my Masters thesis to a more encompassing, applied (not precluding any other, potentially less technical research required for this side!) project drawing on the findings and putting together a production-level output, in order to drive the Research Lab and Core Modules in turn. I would find it particularly exciting to set up a study and formulate research questions as it comes to applications, possibly collaborating with institutes like Institute of Integrated Study at JKU or industry partners, of which there are some who are also interested in accessibility topics in Linz too.

At the same time I think year 1's first term's Core Module (Computational X) Electives' flexibility will allow for meaningful and complemnetary knowledge and practical skills, and later, in second term, a rounding out of research focus areas by way of the gained research methodologies, in the Research Labs.

I expect to deal with topics fully embedded in the IT:U NLP Group's focus areas by the time second term comes at the latest.

Focus Areas of Interest

- Governance of Large Language Models - my specific interest

- Knowledge and Reasoning (broadly)

I am gravitating toward the intersection of linguistic competence as outlined in the paper under discussion in the above and more explicit knowledge questions and task applications of LLMs as in my own work, I am finding. From this view I might also count Computational Argumentation and Fact-checking, especially also with a view to exciting applications, as the third NLP group focus area of interest.

I come from what I might call Symbolic-Augmented NLP and developing robust and explainable AI systems that integrate symbolic reasoning with LLMs, drawing on my background in symbolic computation and current work at Masters level in XAI, as well as industry experience with Wolfram Research where such a project is under way at production grade and scale. RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is of particular interest in this context and something I want to formally incorporate into my Masters thesis as well.

Bringing It Back to Governance

Linguistic competence, benchmarking in general, specific task measurements, symbolic frameworks: My intuition is that these can all be brought under the banner of Governance and that this will be a core LLM topic informed by applications areas as well. I would be excited to enter into a PhD program with this general research focus, and a core project like Making PDFs Accessible and Barrierfree an initial handle on this larger area, spinning off into practice-informed and/or existing research focus driven concerns throughout year 1, to settle on a concrete question by year 2, in time for the PhD Thesis Proposal.

Project Assistance

I understand and note this is an application for a four-year job as well as a research position! I see the project assistance outlined in the curriculum overview for years 2 - 4, and actually see myself in a potentially more technical role drawing on my AI and software engineering studies in the IT:U lab context as well, but am open to the group's needs of course.

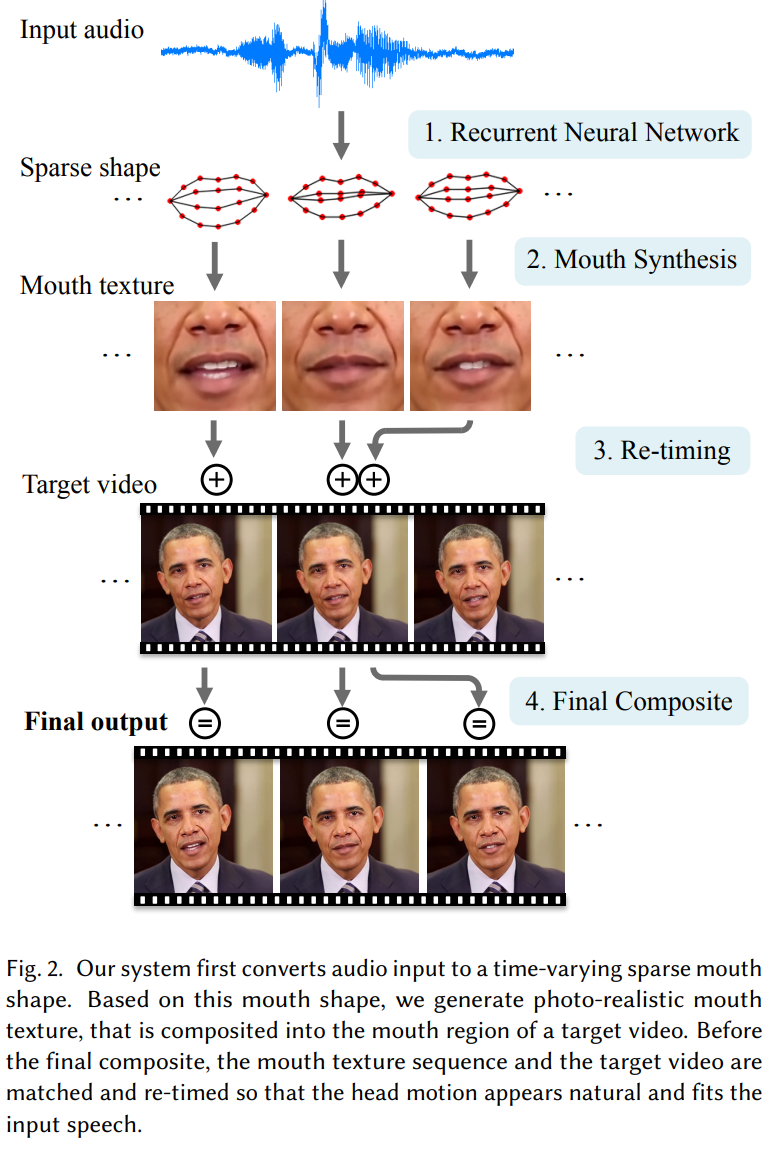

Play and Exploration

One hallmark of IT:U is undoubtedly its lab setup. Something I can absolutely imagine exploring by intertwining it with a topic like linguistic competence, on the one hand, and something like the motion tracking studio or maker lab resources (pis, cameras, proxies), is transcending LLM language capabilities into other competences, like also feeding body pose or facial expression to an LLM and testing an embodied/agentic model, pushing for really natural language processing, in the sense of the richness of human communication. I am sure there would be opportunities for side projects of this sort along the way too, maybe also again tying in with Ars Electronica, a partner of IT:U especially at the Founding Lab stage (still on the IT:U website footer too).

The JKU-IT:U Linz Dornach Microcosm

JKU's Student Union hosts AI Get-Togethers at KHG, the Catholic University Society (and especially the Cellar Bar, a popular evening destination in the university area) and Neuron AI is a JKU Masters student grouping that visits to reads papers, also meeting at KHG: I literally live here, having found a home and a community, and have expressed elsewhere in my application materials that I see myself in a potential role facilitating the exchange, bringing in IT:U (maybe especially its AI-interested groups) into the fold as well, as this new university not only makes its mark, but integrates itself into existing academic circles locally as well! I would be absolutely honored to play that role in fact, if it makes sense, and as I take a moment from my Masters studies to envison what this might look like.

Obligatory Note

Of course, projecting into the future is hard, and all I can hope to do here is outline a sense of direction and check my own alignment with these propositions, as they become less vague and will undoubtedly be influenced by the group's existing research agenda, academically speaking.

Side Note: Timelines and Flexibility

I consider myself the kind of person that can definitely keep a deadline and even speed if needed. I also do my homework. So if in the case of accceptance, faster Masters completion or preliminary work (I am thinking of paper reading homework to hit the ground running come summer 2025) is needed, I am open to being flexible in this way and want to signal my readiness to do what it takes, also to close any gaps in my preparation for undertaking this PhD, if there are some.

Own Questions

5 mins

- NLP Group Decisions Timeline? Helps me balance progress in other applications.

- Comp. X PhD Program/NLP Group Applications, and if this can be shared: how many applications to the NLP group were there? How many applicants were shortlisted for interview?

- (Future growth anticipation: will there be positions next year?)

- Collaboration plans: Overlap/ideas for collaboration within IT:U, with other groups? Ideas/anything concrete for collaboration with JKU, or industry in Linz? ("Looking at you, NXAI")

- There probably will not be time today, but my group in a JKU XAI course was curious if there are any topics in Knowledge Graphs you are currently pursuing or would consider pursuing, going from your work on Al-Katib, Hou et al.. See also below.

Dear Yufang, thank you for the interview, and I will make sure to share a direct link to these prep notes and presentations immediately before, during or after my interview January 9th morning.

XAI Project: End-to-End Argumentation Knowledge Graph Construction

TLDR: We go from an initial interactive visualization test of the Knowledge Graph described in Al-Katib, Hou et al. to three standard explainable AI (XAI) approaches to explore a modern BERT implementation of the model discussed in the second part of the paper, on auto-labeling claims, by picking a subset of the tasks down-stream of an initial concept-prediction. Concept-prediction was poor but down-stream task performance improved, even with poorly predicted concepts, which was suprising. By tweaking both model and dataset we believe we could deliver better performance in future work (university Masters level class project, group of 4).

The bulletpoints of the final presentation I held on December 11th, 2024, at JKU Linz (AI and Visualization) follow here summarily:

The Knowledge Graph (KG)

We work with a dataset representable as KG ultimately, the main features of interest being Input.Claim, Input.Concepts and Input.Stance as well as as Answer.Relation.

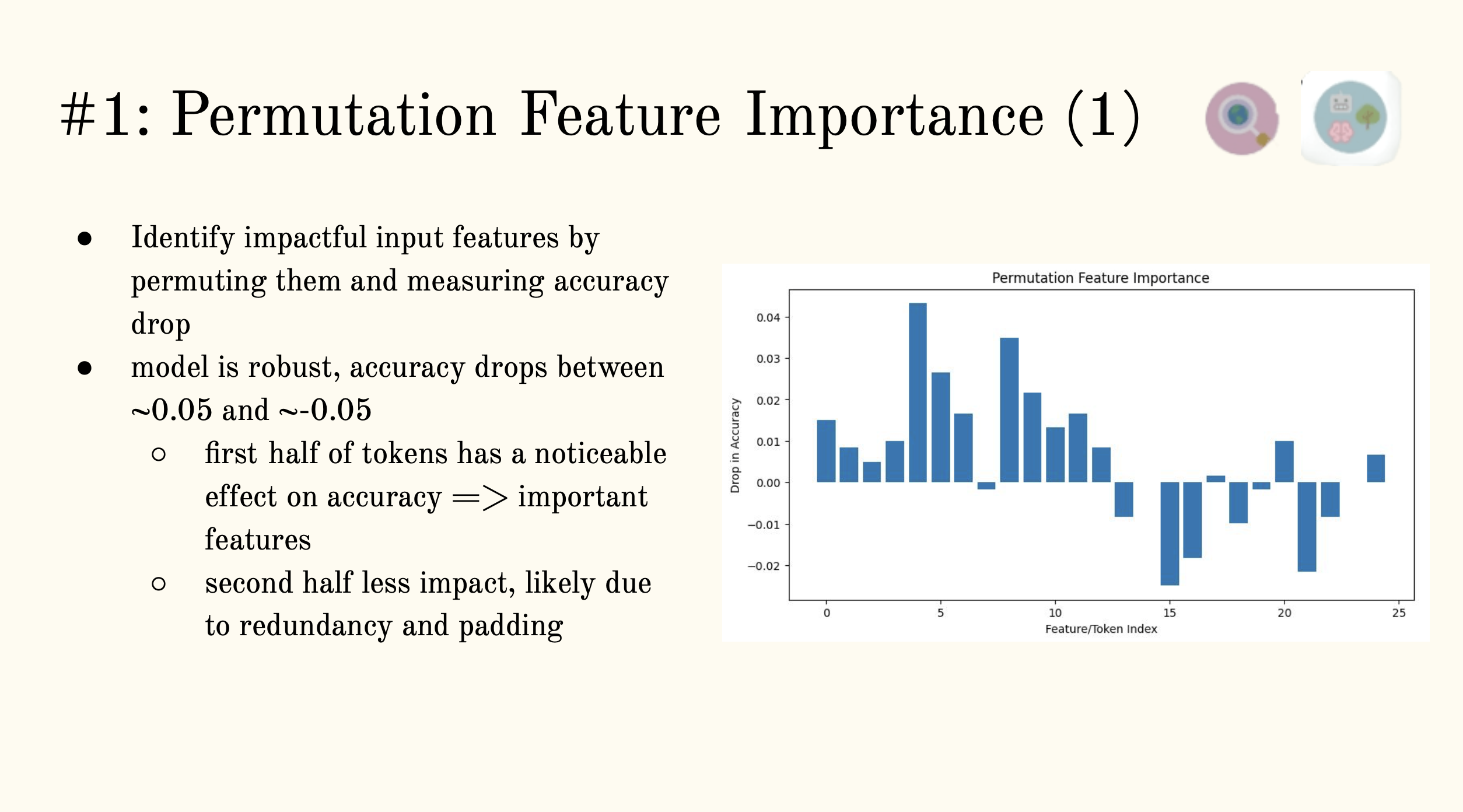

Permutation Feature Importance (PFI)

To understand global feature importance we shuffle feature values across the dataset.

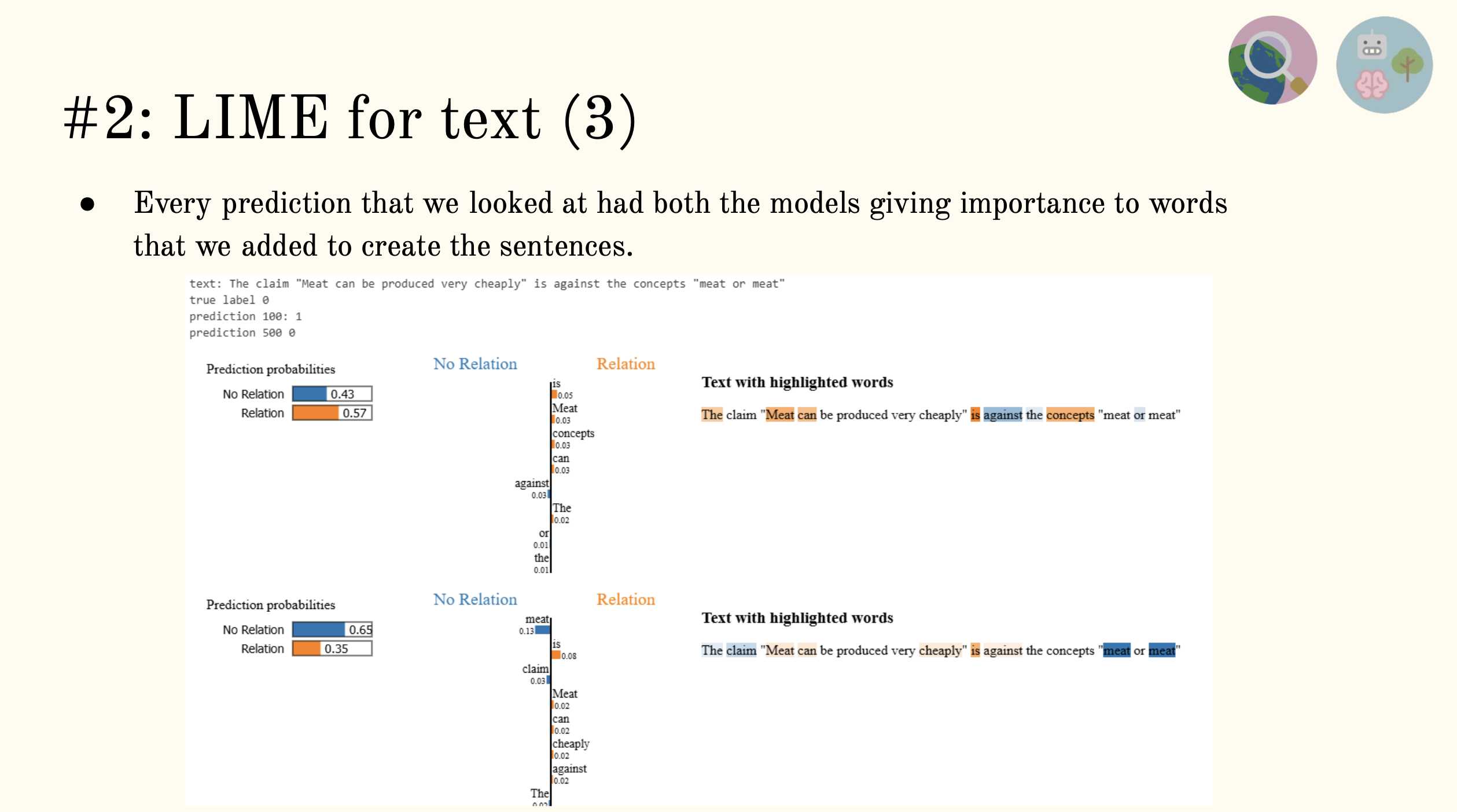

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME)

With LIME we locally explain predictions, paying attention to word oder mainly (Input.Claim), inspired by our findings from PFI.

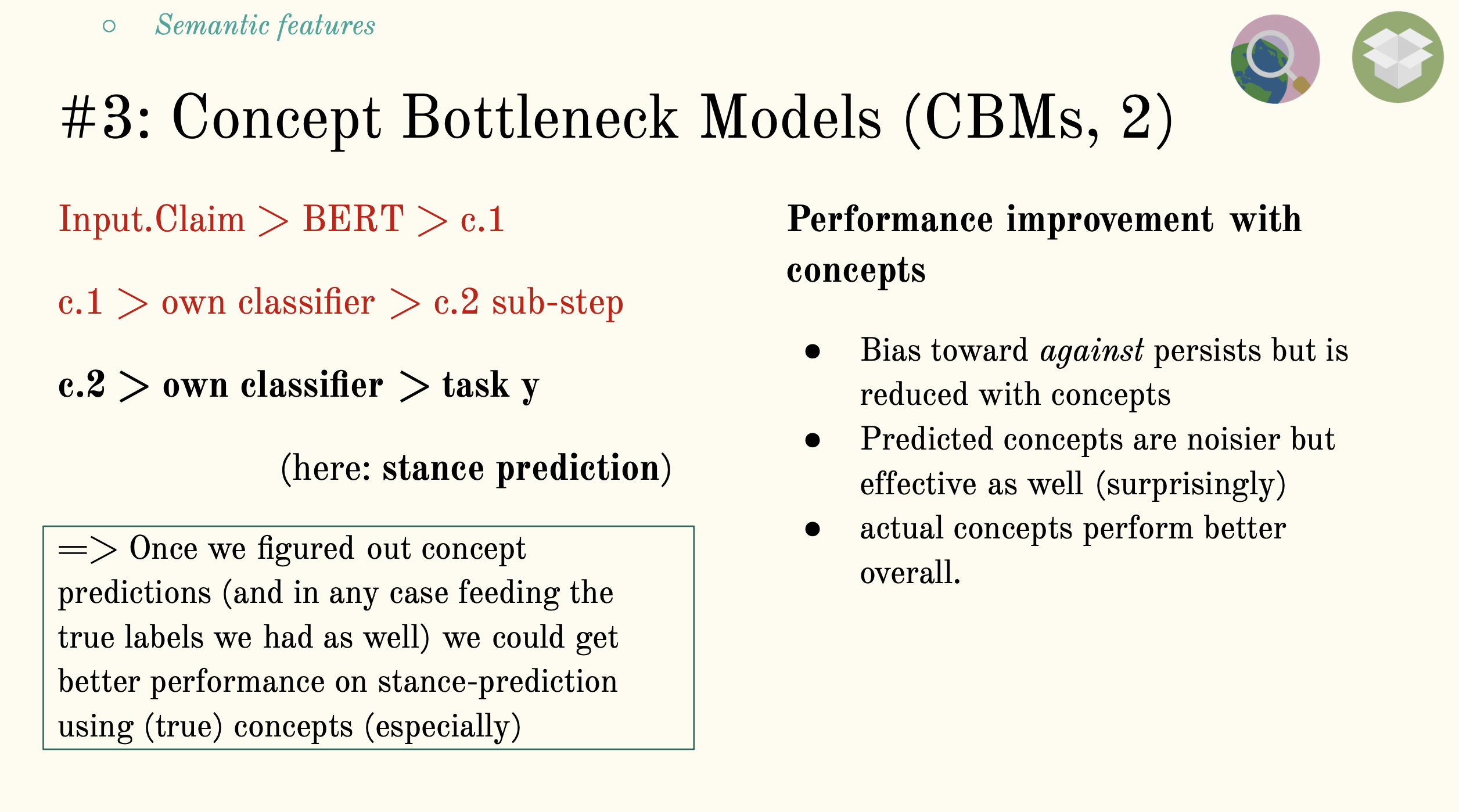

Concept Bottleneck Model (CBM)

Our dataset contains concept labels actually, so we are really dealing in concepts at a data level, but we are interest in applying concept-based techniques to our explaining as well, also at model level, where we introduced BERT representations already at PFI stage: we don't currently have the model, but contact with the researchers suggests this is an addition. We are interested specifically in predicting Input.Stance based on both Input.Concept predictions as well as the true labels.

The intersting thing, our takeaway, is that both our noisy concept predictions and the true labels aid performance in .Stance prediction as a down-stream task: this motivates us to carry out further research on improving model and down-stream task performance!

Links:

wsrp 2024

After being a student myself in the Wolfram Summer School (for adults) in 2023, I am grateful for the opportunity to mentor some great high school students in completing their projects and return the favor in that way.

The 2024 iteration of the Wolfram Summer Research Program is now complete: the following are the student projects I had a part in.

-

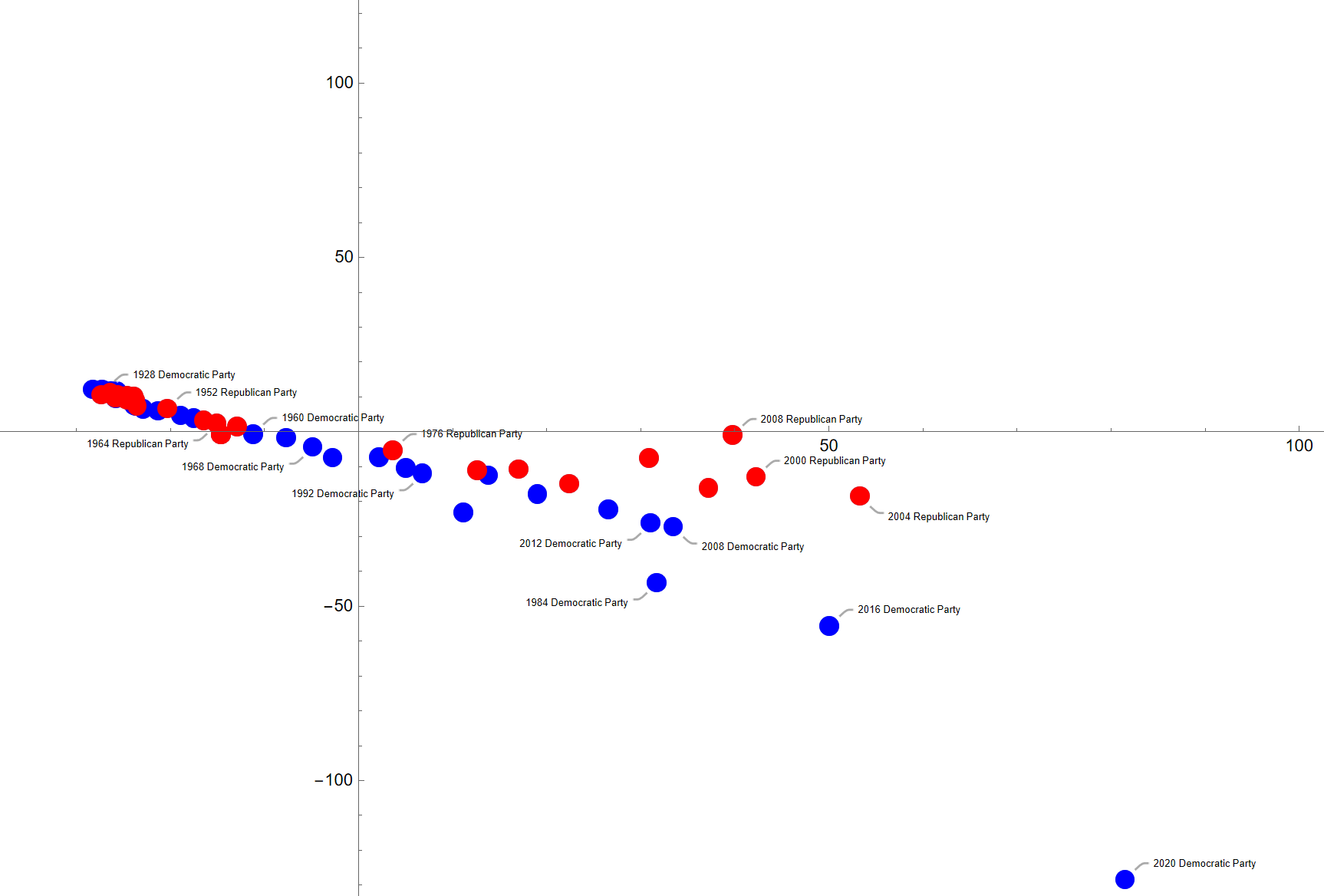

Applications of LLMs in Political Science

Applications of LLMs in Political ScienceHere we test out some NLP functionality built into WL, to answer questions like: why is the 2020 Democrat party platform an outlier in some way to both other Democrat and Republican platforms? Super interesting in this project: WL in the "computational language" idea, knitting together NLP-functionality here. We also did LLM-data-annotation and a comparision of LLM classification with traditional methods like PCA (Principial Component Analysis) on the way.

-

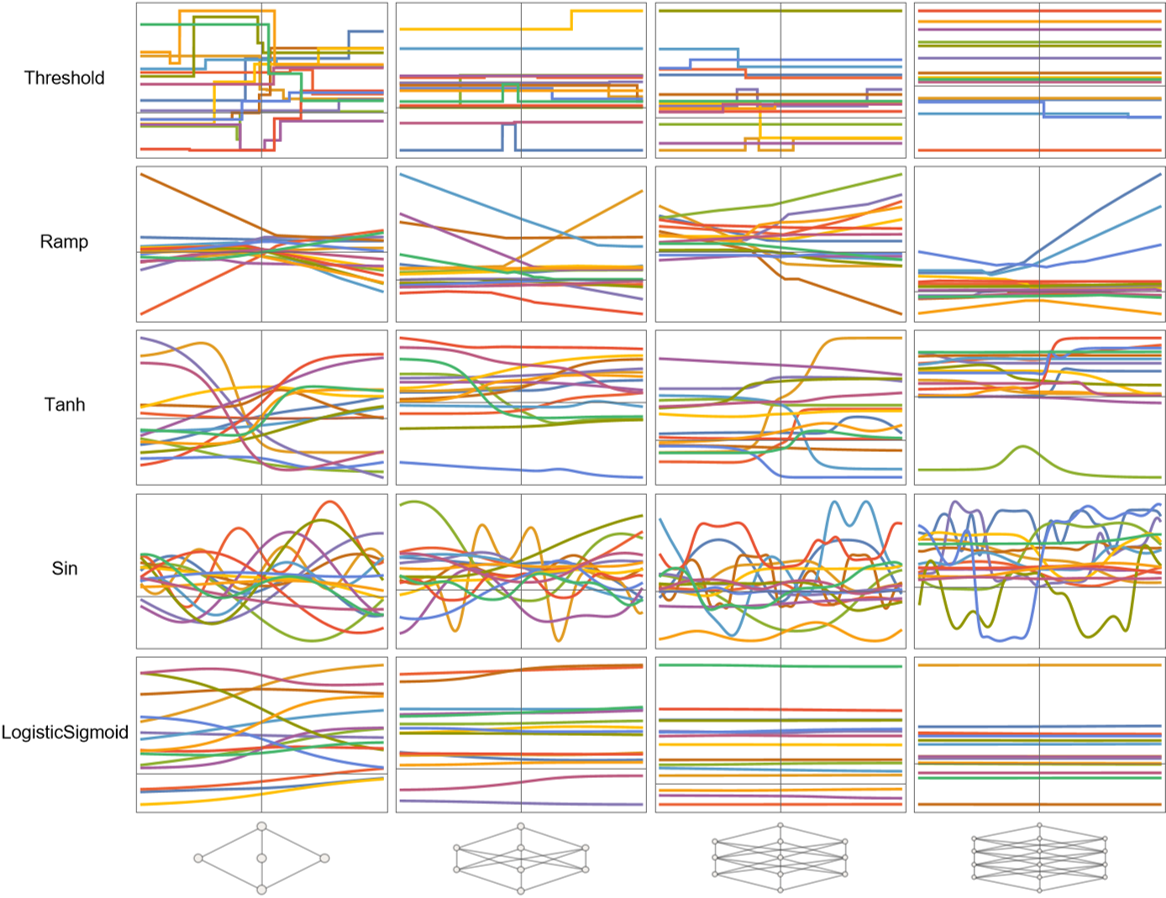

Analyzing Neural Nets in Wolfram Language: Weight Initialization (Untrained Nets)

Analyzing Neural Nets in Wolfram Language: Weight Initialization (Untrained Nets)This was a study of the effects of randomly generated weights and biases on distributions of outputs of untrained neural networks, with special attention paid to activation functions. Super interesting in this project: WL handling of neural networks at the initialization stage, neural nets in Mathematica environments generally.

-

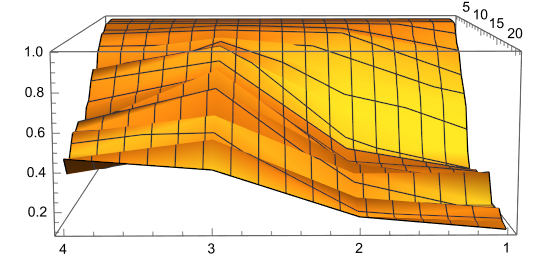

Analyzing Neural Nets in Wolfram Language: Weight-Noising (Trained Nets)

Analyzing Neural Nets in Wolfram Language: Weight-Noising (Trained Nets)Finally, we took a look at the impact of parameter perturbation on neural network performance. Super interesting in this project: WL manipulation of neural nets after training, neural nets in Mathematica environments generally

The Wolfram Summer Research Program is a project-based research opportunity for motivated high-school students to move beyond the cutting edge of computational thinking and artificial intelligence.

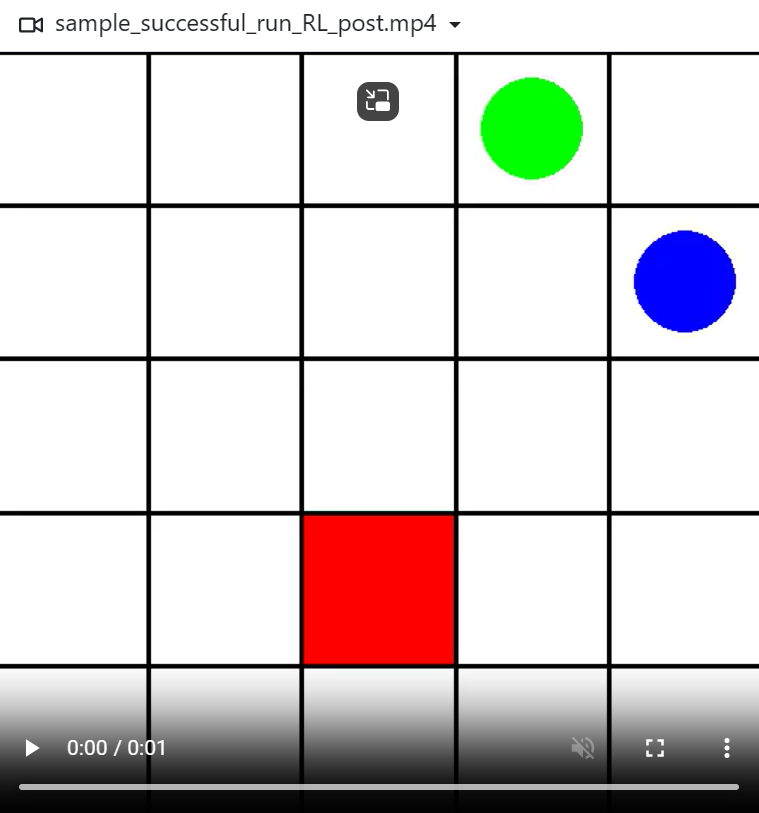

Reinforcement Learning Goes Deep

Now for a short, project-oriented piece on Deep Reinforcement Learning, building mainly on challenge 2 of 3 in the exercise portion for JKU's Deep Reinforcement course - 10/10, would-recommend. I'll also point to my Part I, Reinforcement Learning without the Depth.

The subject of the task is Minigrid - but the main training/debugging will happen in the slightly dumbed down version:

If scale is the only difference, and the problem of finding a key and opening a door can be encoded in a grid, we can definitely imagine a host of more increasingly complex application scenarios for the same approach.

Recap of the Basics

Through the lens of a mini-grid challenge.

Value-Function: Estimates how good it is for the agent to be in a given state. More formally: "Expected return of a state $s$ when following the policy $\pi$." (We want to maximize our future rewards.)

Therefore it depends on:

- current policy $ \pi $

- environent transition dynamics

- reward function

- discount factor gamma

In a formula:

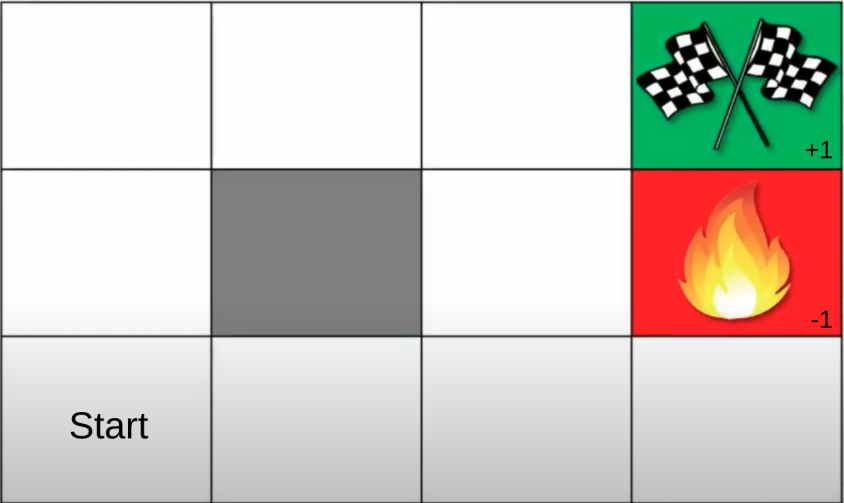

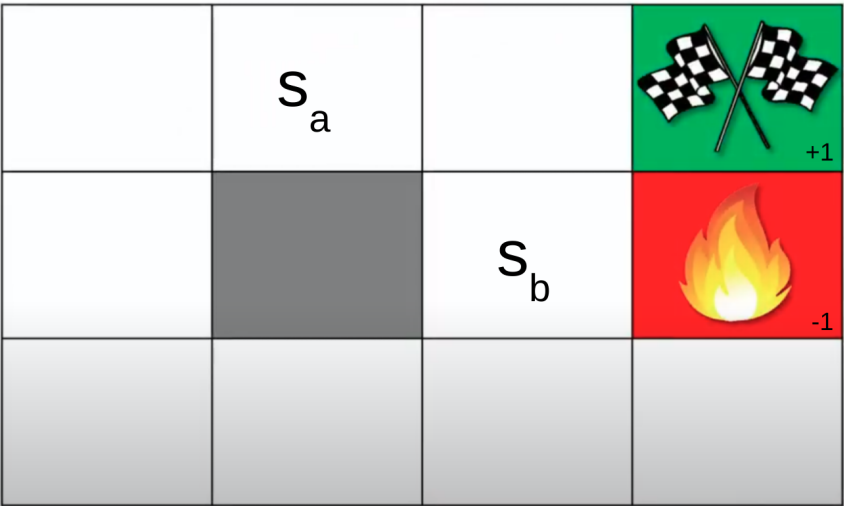

\[V_{\pi}(s) = E_{\pi} \left[ R_t | s_t = s \right] = E_{\pi} \left[ \Sigma_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+1} | s_t = s \right]\]The return is the sum of our future rewards. Visual intuition for the grid setting goes something like this:

The action is a function of the policy, and the rewards depends on the action, to link the dependencies up.

Q-Function: The Q-Function tells us how good the action is given a particular state. Formally: "Expected return of taking the action $a$ in state $s$, and following policy $ \pi $ afterwards." The relation between optimal $V$ (Value) and $Q$ function is direct:

\[V^*(s) = max_a Q^*(s, a)\]Computation of the Q-Function:

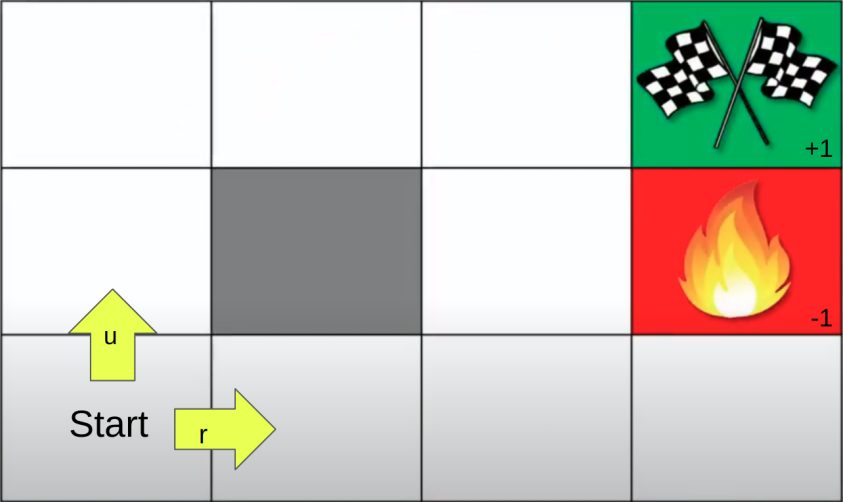

\[Q_{\pi}(s, a) = E_{\pi} \left[ \Sigma_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+1} | s_t = s, a_t = a \right]\]To illustrate an example using the grid intuition we took a moment ago, together with optimal Q- and V-functions (highest values over fall Q-/V-functions), we work a Q-learning example (where Q-learning comes from Dynamic Programming and the approach of braking down a big problem into small problems - DQN is the Deep Learning extension, see the famous paper that introduced it about a decade ago, by playing Atari with this method) where the agent move u(p) and r(ight):

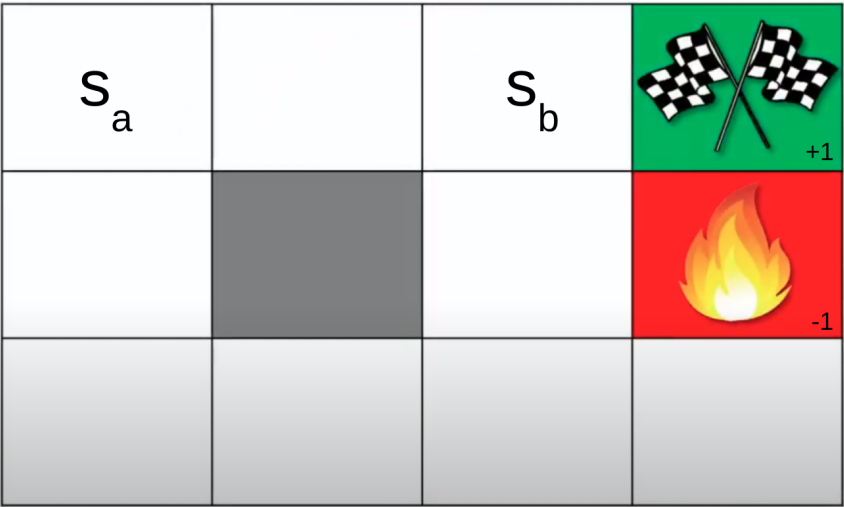

The policy where the target (+1) is hit more often is the optimal policy, in turn determining optimal V-/Q-Function. Again, V is about state and Q is about action, they go together.

In general in this scenario …

… $s_b$ is probably in a more optimal situation (V) compared to $s_a$, but here …

… $s_b$, being closer to the danger area, might actually not be more optimal.

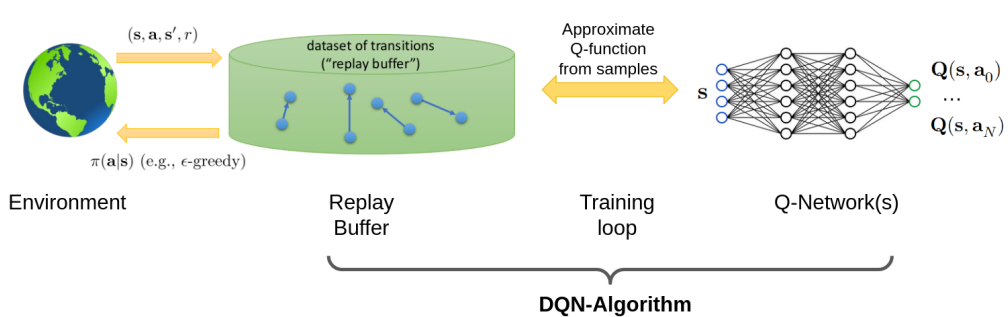

Deep Q-Learning Algorithm: Let's start with an overview.

The Replay Buffer, a particular data set, is the core component. It is also, just like Neural Nets, somehow inspired by biology and animal learning, where the sleep and dream process, selecting examples from the preceeding day, affects future behaviour, i.e. learning is contingent upon some sort of delayed replay.

In the ML view however, the Replay Buffer essentially breaks correlation in the data, by randomly sampling the data.

As far as the algorithm goes, the training loop for DQN minimizes the Temporal Difference (TD) error. TD is just the local improvement as far as the state is concerned, taking into account the currently available best return.

DQN Algorithm Pseudocode

- Initialize Replay Memory $B$ with Capacity $M$

- Initialize Q function with network $\Theta$

- Initialize Q target function with network $\Theta^{'}$

- Initialize environment:

env = env.make("name_of_env") - Add preprocessing wrappers:

env = wrap(env) - Initialize more: exploration factor $\epsilon$, learning rate $\alpha$, batch size $m$, discount factor $\gamma$, any other hyperparameters.

- For $episode = 1$ to $N$ do:

st = env.reset()- While not done do:

- With probability $\epsilon$ select random action $a_t$

- Otherwise select: a_t = $argmax_a Q(s_t, a; \Theta)$

- $s_{t+1}, r_t, d_t,$ _ =

env.step(at) - Store transition: $(s_t, a_t, r_t, s_{t+1}, d_t)$ in $B$

- Sample random batch from memory $B$: $(s_j, a_j, r_j, s_{j+1}, d_j)$

- Targets: \(y_j = \begin{cases} r_j \text{ for terminal }s_{j+1} \\ r_j + \gamma \cdot max a Q(s_{j+1}, a; \Theta^{'}) \text{ for non-terminal }s_{j+1} \end{cases}\)

- Loss: $L(\Theta) = (y_j − Q(s_j, a_j; \Theta))^2$

- Update $\Theta$: $\Theta \leftarrow \Theta − \alpha \cdot \nabla L(\Theta)$

- End while

- Update target network $\Theta^{'}$: $\Theta^{'} = \tau \cdot \Theta + (1 − \tau) \cdot \Theta^{'}$

- End for

The Challenge

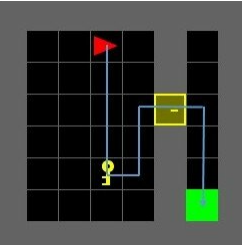

The challenge is to solve this environment: "Minigrid contains simple and easily configurable grid world environments to conduct Reinforcement Learning research. This library was previously known as gym-minigrid." (MiniGrid)

So it is about making the agent collect the key, unlock the door and reach the goal in this 6x6-grid.

Characteristics:

- State space: Symbolic, non-image observation $(3,7,7)$

- Action space: 7 discrete actions

- Reward range: $[0,1]$

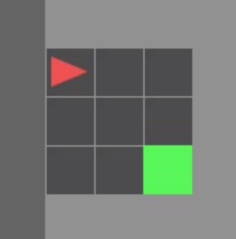

This 3x3/5x5 (incl. wall) version can be considered a dumbed down version usable for initial training and debugging:

This is an example of the Minigrid Empty

The Approach (with Code)

So I did take the approach of working with the 5x5 version of the grid to get a working prototype.

The main logic is reproduced here/full repo on GitHub.

MiniGrid

# Minigrid Environment

from minigrid.wrappers import ImgObsWrapper

class ChannelFirst(gym.ObservationWrapper):

def __init__(self, env):

super().__init__(env)

old_shape = env.observation_space.shape

self.observation_space = {}

self.observation_space = gym.spaces.Box(0, 255, shape=(3, 7, 7))

def observation(self, observation):

return np.swapaxes(observation, 2, 0)

class ScaledFloatFrame(gym.ObservationWrapper):

def __init__(self, env):

gym.ObservationWrapper.__init__(self, env)

def observation(self, observation):

# careful! This undoes the memory optimization, use

# with smaller replay buffers only.

return np.array(observation).astype(np.float32)

class MinigridEmpty5x5ImgObs(gym.Wrapper):

"""Minigrid with image observations provided by minigrid, partially observable."""

def __init__(self, render=False):

if render:

env = gym.make('MiniGrid-Empty-5x5-v0', render_mode="rgb_array")

else:

env = gym.make('MiniGrid-Empty-5x5-v0')

env = ScaledFloatFrame(ChannelFirst(ImgObsWrapper(env)))

super().__init__(env)

class MinigridDoorKey6x6ImgObs(gym.Wrapper):

"""Minigrid with image observations provided by minigrid, partially observable."""

def __init__(self, render=False):

if render:

env = gym.make('MiniGrid-DoorKey-6x6-v0', render_mode="rgb_array")

else:

env = gym.make('MiniGrid-DoorKey-6x6-v0')

env = ScaledFloatFrame(ChannelFirst(ImgObsWrapper(env)))

super().__init__(env)

The Actual (Policy) NN

class MlpMinigridPolicy(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_actions=7):

super().__init__()

self.num_actions = num_actions

self.fc = nn.Sequential(nn.Flatten(),

nn.Linear(3*7**2, 256), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(256, 256), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(256, 64), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(64, num_actions))

def forward(self, x):

if len(x.size()) == 3:

x = x.unsqueeze(dim=0)

return self.fc(x)

Terget Network Update Strategy

# Update Target network

def soft_update(local_model, target_model, tau):

"""Soft update model parameters.

θ_target = τ*θ_local + (1 - τ)*θ_target

Params

======

local_model (PyTorch model): weights will be copied from

target_model (PyTorch model): weights will be copied to

tau (float): interpolation parameter

"""

# TODO: Update target network

for target_param, local_param in zip(target_model.parameters(), local_model.parameters()):

target_param.data.copy_(tau*local_param.data + (1.0-tau)*target_param.data)

Training Loop Using the Target Network Update and Hyperparams from Above

from torch.serialization import load

# Train the agent using DQN for Pong

returns = []

returns_50 = deque(maxlen=50)

losses = []

buffer = ReplayBuffer(num_actions=num_actions, memory_len=buffer_size)

dqn, dqn_target, timesteps = load_checkpoint(load_path)

optimizer = optim.Adam(dqn.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

mse = torch.nn.MSELoss()

state = env.reset()[0] # !

for i in range(num_episodes):

ret = 0

done = False

while not done:

# Decay epsilon

epsilon = max(epsilon_lb, epsilon_ub - timesteps/ epsilon_decay)

# action selection

if np.random.choice([0,1], p=[1-epsilon,epsilon]) == 1:

action = np.random.randint(low=0, high=num_actions, size=1)[0]

# print("selected random action")

else:

# state_tmp = state[np.newaxis, :].astype(np.float32)

state_tensor = torch.tensor(state, dtype=torch.float32, device=device)

net_out = dqn(state_tensor).detach().cpu().numpy()

action = np.argmax(net_out)

# print("selected q-optimal action")

# next_state, r, done, info = env.step(a)

next_state, r, terminated, truncated, info = env.step(action)

done = terminated or truncated

# print(next_state.shape)

ret = ret + r

# TODO: store transition in replay buffer

buffer.add(state, action, r, next_state, done) # (state, action, ret, next_state, done)

state = next_state

timesteps = timesteps + 1

# update policy using temporal difference

if buffer.length() > minibatch_size and buffer.length() > update_after:

optimizer.zero_grad()

# TODO: Sample a minibatch randomly

states, actions, rewards, next_states, dones = buffer.sample_batch(minibatch_size)

# Convert data to tensors

states = torch.tensor(states, dtype=torch.float32, device=device)

next_states = torch.tensor(next_states, dtype=torch.float32, device=device)

#actions = torch.tensor(actions, dtype=torch.long, device=device)

#rewards = torch.tensor(rewards, dtype=torch.float32, device=device)

#dones = torch.tensor(dones, dtype=torch.float32, device=device)

# TODO: Compute q values for states

#current_Q_values = dqn(states).gather(1, actions)

#print("current_Q_values shape: ", current_Q_values.shape)

current_Q_values = dqn(states)

# TODO: compute the targets for training

max_Q, _ = torch.max(dqn_target(next_states), dim=1)

#next_Q_values = dqn_target(next_states).max(1)[0].detach()

#print("next_Q_values shape: ", next_Q_values.shape)

Q_targets = rewards + (1 - dones) * gamma * max_Q

# TODO: compute the predictions for training

#expected_Q_values = rewards + (gamma * next_Q_values * (1 - dones))

Q_predictions = current_Q_values.gather(1, actions.argmax(1, keepdim=True)).squeeze()

# TODO: Compute loss: mse = mean squared error

loss = mse(Q_predictions, Q_targets) # Q_targets.unsqueeze(1)

# Print the loss

#print(f"Loss at timestep {timesteps}: {loss.item()}")

#print('predictions', current_Q_values.shape, 'targets', expected_Q_values.unsqueeze(1).shape)

#print(loss)

loss.backward(retain_graph=False) # retain_graph=False ?

optimizer.step()

losses.append(loss.item())

# Update target network

soft_update(dqn, dqn_target, tau)

if done:

state = env.reset()[0]

print(f"Episode: \t{i}\t{ret}\t{datetime.now().strftime('%Y_%m_%d-%H_%M_%S')}")

break

returns.append(ret)

returns_50.append(ret)

if i % 50 == 0:

store_checkpoint(checkpoint_path=save_path, dqn_net=dqn, timesteps=timesteps)

print('\rEpisode {}\tAverage Score: {:.2f}'.format(i, np.mean(returns_50)))

Note: Some debugging lines and TODO comments still in there - here's the difference between ML experiment code and (production) engineering code.

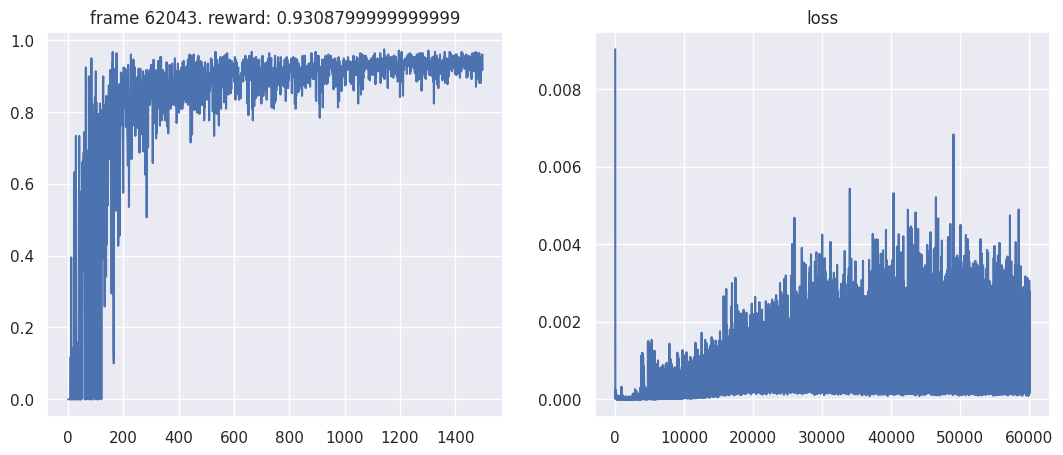

Final Report (submitted with the project repo and the model attaining highest scores possible)

Overview

This report outlines the implementation of a Deep Q-Network (DQN) agent trained to play the game Pong. The agent learns through interaction with the environment, utilizing Q-learning with experience replay to update its policy.

Training and Evaluation Outcomes

Evaluation: Highest score category on the leaderboard (0.965 averaged score in the evaluation script (challenge server)).

Neural Network Architecture

- Model: Deep Q-Network (DQN)

- Layers:

- Fully Connected Layers: Four layers with ReLU activation.

- Output Layer: Outputs Q-values for each action - this is the MiniGrid Policy.

Training Process

Environment and Hyperparameters

- Environment: MiniGrid: MinigridEmpty5x5ImgObs to start, then MinigridDoorKey6x6ImgObs once stabilized learning was achieved.

- Hyperparameters:

- Learning Rate: 1e-3

- Replay Buffer Size: 100000

- Minibatch Size: 256

- Gamma (Discount Factor): 0.9

- Epsilon Decay: 100000 (decay epsilon in 100.000 timesteps)

- Epsilon Lower Bound: 0.3

- Epsilon Upper Bound: 1.0

- Target Network Update Rate ($\tau$): 1e-3

- Number of Episodes: 1500 (marginally better than 1000, and even 800)

Replay Buffer

- Purpose: Stores experience tuples (state, action, reward, next state, done).

- Functionality: Supports adding new experiences and sampling random mini-batches for training.

Experience Report

I think the exercise was a really helpful way to get a grasp on the concepts by filling in the essential gaps. I liked this emphasis on understanding over code volume (lines of code). Testing the hyperparameters and being able to rely on boilerplate functionality that would otherwise just be googled anyway is also really super.

So the core learning for me was the replay buffer for minibatch sampling of tranisitons, review of epsilon greedy exploration vs exploitation, Q-values and Bellman Equation* computation, training with the computed Q-values as targets using a releatively simple NN structure encoding states.

I used Google colab for this project and could train the 5x5 grid in less than 5 minutes for ca. 1000 episodes and then the 6x6 in about 15 minutes.

*The Bellman equation is a fundamental concept in reinforcement learning that provides a recursive decomposition of the value function. In the context of Q-learning, the Bellman equation helps to determine the optimal Q-values for state-action pairs.

In Q-learning, the agent aims to learn a policy that maximizes the cumulative reward by estimating the Q-values, which represent the expected return (cumulative reward) of taking a particular action in a given state and following the optimal policy thereafter.

The Bellman equation for Q-values is expressed as:

\[Q(s, a) = \mathbb{E}[r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') \mid s, a]\]Where:

- \(Q(s, a)\) is the Q-value for taking action \(a\) in state \(s\).

- \(r\) is the immediate reward received after taking action \(a\) in state \(s\).

- \(\gamma\) (gamma) is the discount factor, which determines the importance of future rewards.

- \(s'\) is the next state resulting from taking action \(a\) in state \(s\).

- \(\max_{a'} Q(s', a')\) is the maximum Q-value for the next state \(s'\) over all possible actions \(a'\).

In Deep Q-Networks (DQN), the Bellman equation is used to update the Q-values. Here's how it is applied in the code:

- Current Q-Values: The current Q-values are computed by passing the current states through the Q-network.

- Target Q-Values: The target Q-values are computed using the rewards and the maximum Q-values for the next states, as predicted by the target network. This is based on the Bellman equation.

- Computing the Loss: The loss is computed as the mean squared error (MSE) between the current Q-values and the target Q-values.

- Updating the Network: The gradients are computed and the network parameters are updated using backpropagation and an optimizer (e.g., Adam).

Some more details to each step:

- Current Q-Values: These represent the agent's current estimate of the expected return for each action in the given states.

- Target Q-Values: These are the more accurate estimates obtained by using the Bellman equation. They take into account the immediate reward and the discounted future rewards.

- Loss Calculation: The difference between the current Q-values and the target Q-values (squared error) is minimized during training, leading the Q-network to improve its predictions over time.

- Update Step: The Q-network is updated using gradient descent to reduce the loss, thereby refining its estimates of the Q-values.

(See Part I.)

Course Presentation/AI Product Analysis: Replika

Short course-presentation about the AI companion app in its current iteration. Includes use case study with persona and AI product improvement, embedded in a critical analysis. I am sure we will see more products along this trend.

This was a JKU group work: I delivered the presentation in May 2024.

Attention via LSTM, the Transformer-Connection

Andrej Karpathy was not the first to point out:

The concept of attention is the most interesting recent architectural innovation in neural networks.

In The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks: check it out for RNN character-level language modeling on several fun datasets.

He goes on to distinguish between soft attention (he likens it to declaring a pointer in C, just it doesn't point to an address, but instead defines an entire distribution over all addresses in the entire memory) and hard attention, where chunks of memory are attended to at a time. This is a good image to have in mind as we move into the topic.

But we take the route though RNNs/LSTM, not directly via Transformers: we will get there, though.

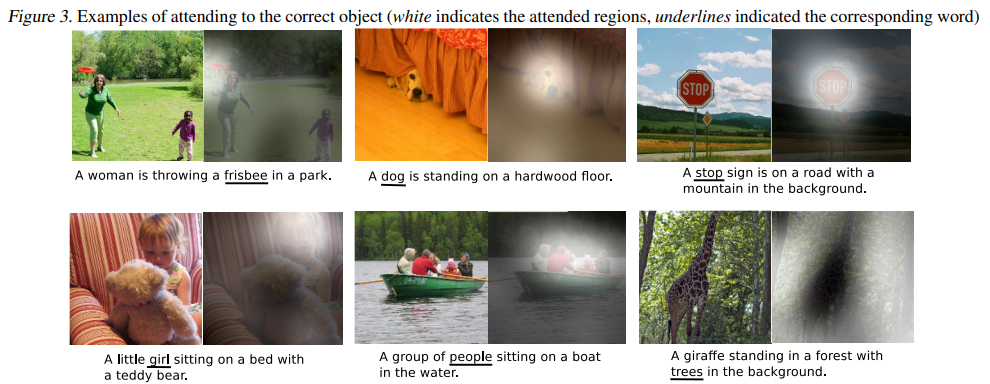

Xu et al. (2015): Spatial Attention

I already talked about this at the end of LSTM in the Linz AI Curriculum. Basically: to make a classification or a prediction, I don't need to pay attention to every detail involved. This makes intuitive sense. Here is how Hochreiter and Adler put it in the LSTM and Recurrent Neural Networks lecture script, which I could not find in a public place online for the moment.

To find an appropriate caption for an image, a distinction between important and dispensable content has to be made.

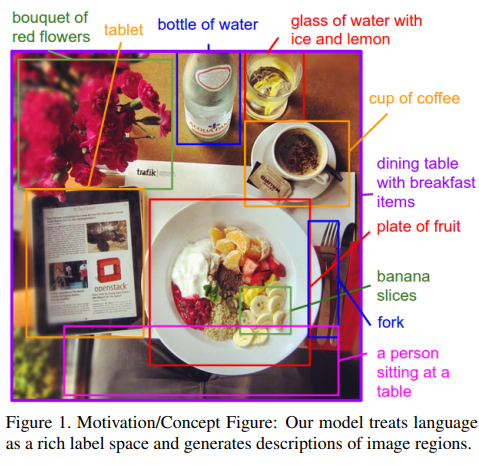

The authors go on to cite Xu, specifically the attention needed for image captioning.

The attention involved in this kind of image captioning is spatial.

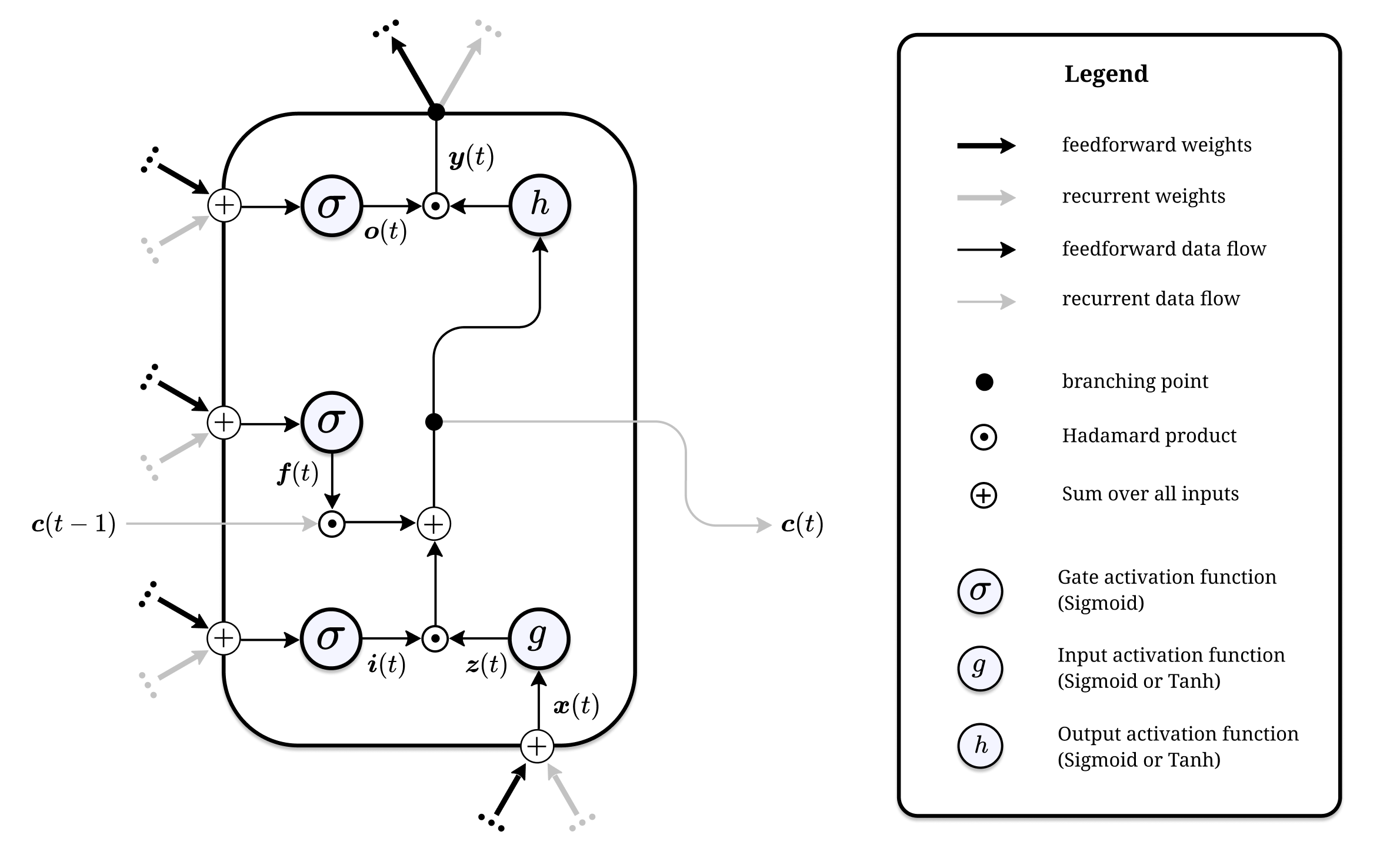

LSTM: Gates Introduced Temporal Attention

Spatial attention is for images and data in more-than-1-D space, whereas temporal attention is for sequences and focuses on the elements (or the intervals) of sequences.

Without explicitly mentioning it, we already have dealt with attention mechanisms. The gating mechanisms of LSTM memory calles have the purpose of controlling which information is used or kept and which information is ignored. Gates can decide wich information enters a memory cell, which information is kept over time, and which information can be disregarded or scaled down. Gating is focusing on a subset of the available information, i.e. it is an attention mechanims.

(Hochreiter and Adler Scriptum)

This is the fundamental insight here.

As an example, consider the input gate of an LSTM memory cell.

\[\begin{align} \boldsymbol{i}(t) &= \sigma\left(\boldsymbol{W}_{i}^{\top} \boldsymbol{x}(t)+\boldsymbol{R}_{i}^{\top} \boldsymbol{y}(t-1)\right) \\ \boldsymbol{z}(t) &= g\left(\boldsymbol{W}_{z}^{\top} \boldsymbol{x}(t)+\boldsymbol{R}_{z}^{\top} \boldsymbol{y}(t-1)\right) \\ \boldsymbol{c}(t) &= \boldsymbol{f}(t) \odot \boldsymbol{c}(t-1)+\boldsymbol{i}(t) \odot \boldsymbol{z}(t) \\ \end{align}\]The input activation vector is of the form \(\boldsymbol{i}(t) \in \left(0, 1\right)^I\). This means that its multiplication with the cell input activation in the final equation above controls which, and to which degree, elements of \(\boldsymbol{z}(t)\) are used to update the cell state. Therefore the elements of \(\boldsymbol{i}(t)\) can be interpreted as the attention \(\boldsymbol{z}(t)\) receives.

In the language that has developed around attention mechanisms in deep learning, the inner product between the kth column of \(\boldsymbol{W}_i\) and the input vector as the attention score \(e_k \in \mathbb{R}\):

\[e_k = \sum_{l=1}^{d} w_{lk} \cdot x_l + (w^*_{k})^\top \cdot x = \|w^*_{k}\| \cdot \|x\| \cdot \cos(\angle(w^*_{k}, x))\]The magnitude of \(e_k\) depends on the product of the norms of \(w^*_{k}\) and \(x\) while the sign depends on the angle. As the magnitude grows and \(w^*_{k}\) and \(x\) in a similar direction, the attention will be high because \(\sigma(e_k) \approx 1\). If the vectors point in opposite directions, attention will be \(\approx 0\).

This way, every column of the weight matrix \(\boldsymbol{W}_i\) can learn to selectively choose input vectors with certain traits. Every entry of the input gate […] is of the form \(\boldsymbol{i_k} \in \left(0, 1\right)\). This can be considered as soft attention to entry \(z_k\), since it can also choose to let through half of the information. Would the gate be either zero or one, i.e. \(\boldsymbol{i_k} \in \left\{0, 1\right\}\), teh gate \(i_k\) is paying hard attention to the entry \(z_k\).

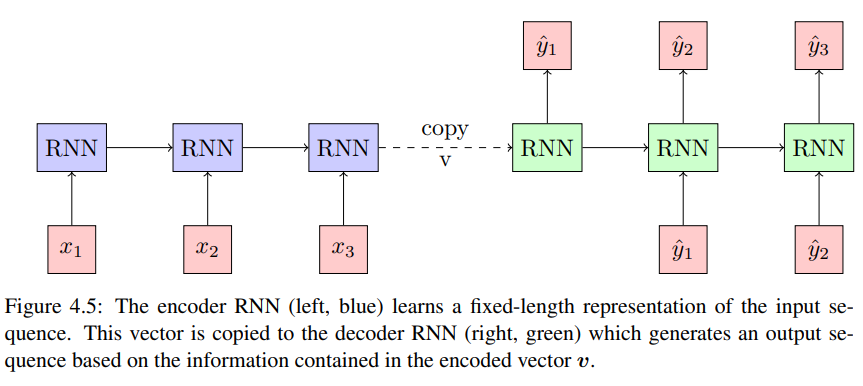

Attention in seq2seq (Sequence-to-Sequence Models)

The basic RNN seq2seq model consists of two networks, the encoder and the decoder, where the encoder reads a sentence of length \(\left( \boldsymbol{x}(t) \right)^T_{t=1}\) of length \(T\) and produces a fixed-dimensional vector representation \(v\) of the whole sequence.

(From Hochreiter and Adler)

Typically \(v\) is the last state \(h_T\) of the encoder network but can also be the last cell state \(c_T\). This approach was introduced by both

- Cho et al. (2014): using GRU.

- Sutskever et al. (2014): in a similar but modified version that uses LSTM.

Regardless of state vector being copied and RNN-Model used, the problem with the approach is that, no matter how complex the input sequence, it needs to be encoded as a whole, to one vector \(v\), rather than being broken down to only the relevant parts. The attention in this model is realized by the encoder RNN.

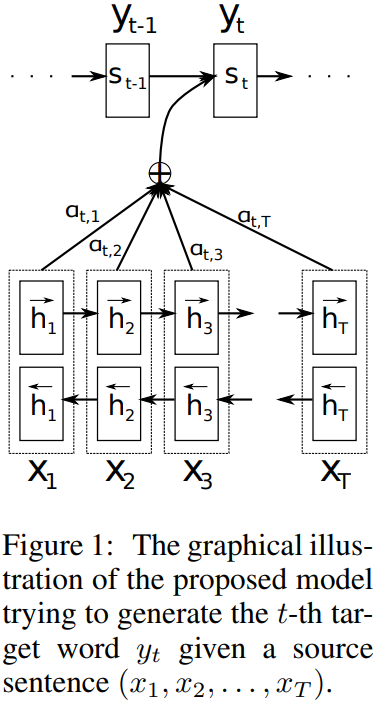

Additive Attention

An early attention mechanism was introduced by Bahdanau et al. (2014), which enhances the encoder-decoder model by enabling it to focus on various parts of the input sequence sequentially. This mechanism is integrated with an alignment process. From the Abstract, highlighting how this ties into their translation task:

The models proposed recently for neural machine translation often belong to a family of encoder-decoders and consists of an encoder that encodes a source sentence into a fixed-length vector from which a decoder generates a translation. In this paper, we conjecture that the use of a fixed-length vector is a bottleneck in improving the performance of this basic encoder-decoder architecture, and propose to extend this by allowing a model to automatically (soft-)search for parts of a source sentence that are relevant to predicting a target word, without having to form these parts as a hard segment explicitly. With this new approach, we achieve a translation performance comparable to the existing state-of-the-art phrase-based system on the task of English-to-French translation. Furthermore, qualitative analysis reveals that the (soft-)alignments found by the model agree well with our intuition.

The encoder uses a bidirectional RNN (BiRNN) to process the input sequence both in the forward and backward directions, generating forward and backward hidden states. These states are combined at each time step to provide a comprehensive view of the input sequence.

The decoder RNN generates the output at each time step based on its current hidden state, the previous output, and a context vector. This context vector is computed using the attention mechanism, which employs an attention vector to create a weighted sum of the encoder's hidden states.

The attention score, which is crucial for computing the attention vector, is determined by a feedforward neural network using the previous hidden state of the decoder and the hidden state from the encoder. This score function is an example of additive attention due to the summation operation inside the tanh function.

The attention score \(e_j(i)\) is in principle an alignment score that determines how well the inputs around position \(j\) and the output at position \(i\) match. The score function is a feedforward neural network with parameters \(\boldsymbol{W}\) and \(\boldsymbol{U}\) and inputs \(\boldsymbol{s}(i − 1)\) and \(\boldsymbol{h}(j)\).

(Hochreiter and Adler, emphasis added)

This feedforward network is jointly trained with the other RNNs and is:

\[e_j(i) = \mathbf{v}^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W} s(i - 1) + \mathbf{U}h(j))\]Where \(\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}, \mathbf{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times 2n}, \mathbf{v} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}\) are the parameters. The dimension \(n\) is the size of the hidden vector in the BiRNN. The sum inside the tanh is where the name of the attention method comes from, as in "additive" attention.

After calculating the attention scores, a softmax function is applied to derive the attention vector, which is then used to compute the context vector as a weighted sum of the encoder's hidden states.

\[a(i) = \text{softmax}(e(i)) c(i) = \mathbf{H}a(i) = \sum_{t=1}^{T} h(t)a_t(i)\]Here \(\boldsymbol{H} = \left( \boldsymbol{h}(1), ..., \boldsymbol{h}(T) \right)\) is a matrix with the hidden units as columns, so \(\boldsymbol{f}_con\) is the matrix-vector product of attention vector and hidden units.

The Bahdanau et al. model illustrated graphically:

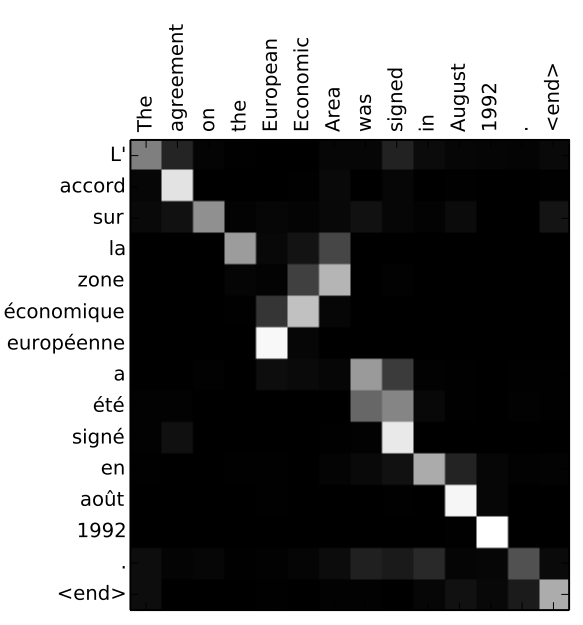

At the attention, level, what is happening? This intensity map ("sample alignments") from the paper illustrates the translation task being treated. Every column is an attention vector.

Multiplicative and Local Attention

Luong et al. (2015) modify the approach. Instead of a bidrectional GRU encoder, multiplicative attention uses a unidrectional stacked LSTM encoder, and in addition to the additive attention (concat in this paper), dot and general score functions are introduced. Taken together, multiplicative attention becomes:

\[e_t(i) = \mathbf{h}(t)^\top \mathbf{s}(i) \quad \text{(dot)}\] \[e_t(i) = \mathbf{h}(t)^\top \mathbf{W} \mathbf{s}(i) \quad \text{(general)}\] \[e_t(i) = \mathbf{v}^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W} [\mathbf{s}(i); \mathbf{h}(t)]) \quad \text{(concat)}\]Attention vector (alignment vector in this paper):

\[a(i) = \text{softmax}(e(i))\]Multiplicative attention is simpler than additive attention. For short input sequences the performance of multiplicative attention is similar to that of additive attention, but for longer sequences additive attention has the advantage.

(Hochreiter and Adler)

Luong et al. (2015) also introduce propose local attention (the idea is to not attend to all hidden units, but only to a subset of hidden units inside a window) in addition to global attention.

Self-Attention

I defer to Hochreiter and Adler for introducing Self-attention via the LSTM network, proposed in Cheng et al. (2016), after citing from the relevant abstract first:

In this paper we address the question of how to render sequence-level networks better at handling structured input. We propose a machine reading simulator which processes text incrementally from left to right and performs shallow reasoning with memory and attention. The reader extends the Long Short-Term Memory architecture with a memory network in place of a single memory cell. This enables adaptive memory usage during recurrence with neural attention, offering a way to weakly induce relations among tokens. The system is initially designed to process a single sequence but we also demonstrate how to integrate it with an encoder-decoder architecture. Experiments on language modeling, sentiment analysis, and natural language inference show that our model matches or outperforms the state of the art.

(Cheng et al. (2016))

So far attention was based on the decoder having access to hidden states of the encoder. Cheng et al. (2016) introduced intra-attention or self-attention where an LSTM network has access to its own past cell states or hidden states. The idea is that all information about the previous states and inputs should be encoded in \(h(t)\). Therefore all relations between states should be induced, which is achieved by intra-attention or self-attention. Toward this end, Cheng et al. (2016) augment the LSTM architecture with a memory for the cell states c and the hidden states (LSTM outputs) \(h\). The memory just stores all past cell state vectors c in a matrix \(C = \left(c(1), . . . , c(t − 1) \right)\) and all past hidden state vectors \(h\) in a matrix \(\boldsymbol{H}(t − 1) = \left(h(1), . . . , h(t − 1)\right)\). Now the LSTM has direct access to its own past states, where the access mechanism is self-attention.

(Hochreiter and Adler)

The formulas for calculating \(\boldsymbol{e}(t)\) and attention vector \(\boldsymbol{a}(t)\) over all previous timesteps \(i = 1, ..., t - 1\) are:

\[e_i(t) = \mathbf{v}^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W}_{hh} \mathbf{h}(i) + \mathbf{W}_{xx} \mathbf{x}(t) + \mathbf{W}_{\tilde{h}\tilde{h}} \tilde{\mathbf{h}}(t - 1))\] \[a(t) = \text{softmax}(e(t))\] \[\mathbf{\tilde{h}} = \mathbf{H}(t-1) \mathbf{a}(t-1)\]Here …

\[\mathbf{H}(t-1) = \left( \mathbf{h}(1), ..., \mathbf{h}(t-1) \right)\]… is the matrix of hidden states up to \(t - 1\).

The attention vector is also applied to all past cell states \(\boldsymbol{C} = \left( \boldsymbol{c}(1), ..., \boldsymbol{c}(t - 1) \right)\):

\[\boldsymbol{\tilde{c}(t)} = \boldsymbol{C}(t-1)\boldsymbol{a}(t-1)\]Once again, to sum up in terms of the formulas for the forward pass:

\[\boldsymbol{i}(t) = \sigma \left( \boldsymbol{W}_i^{\top} \boldsymbol{x}(t) + \boldsymbol{R}_i^{\top} \boldsymbol{\tilde{h}}(t) \right)\] \[\boldsymbol{o}(t) = \sigma \left( \boldsymbol{W}_o^{\top} \boldsymbol{x}(t) + \boldsymbol{R}_o^{\top} \boldsymbol{\tilde{h}}(t) \right)\] \[\boldsymbol{z}(t) = \sigma \left( \boldsymbol{W}_z^{\top} \boldsymbol{x}(t) + \boldsymbol{R}_z^{\top} \boldsymbol{\tilde{h}}(t) \right)\] \[\boldsymbol{c}(t) = \boldsymbol{\tilde{c}}(t) + \boldsymbol{i}(t) \odot \boldsymbol{z}(t)\]Note: \(\odot\) signifies the Hademard-product.

\[\boldsymbol{h}(t) = \boldsymbol{o}(t) \odot tanh(\boldsymbol{c}(t))\]LSTM with self-attention is called Long Short-Term Memory-Network (LSTMN).

Self-attention can be applied at the level of sentences, as in (Lin et al. (2017))[https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.03130]. From the abstract:

This paper proposes a new model for extracting an interpretable sentence embedding by introducing self-attention. Instead of using a vector, we use a 2-D matrix to represent the embedding, with each row of the matrix attending on a different part of the sentence.

The authors use a bidirectional LSTM encoder as in Bahdenau et al. (2014), discussed earlier.

Key-Value Attention

The final form of attention to be highlighted, in order of development, is Key-Value Attention. So far we have performed attention like so: The calcuation of an attention score \(\boldsymbol{e}\), the transformation of the score to an attention vector \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and then the we calculated the context vector (glimpse) \(\boldsymbol{c}\).

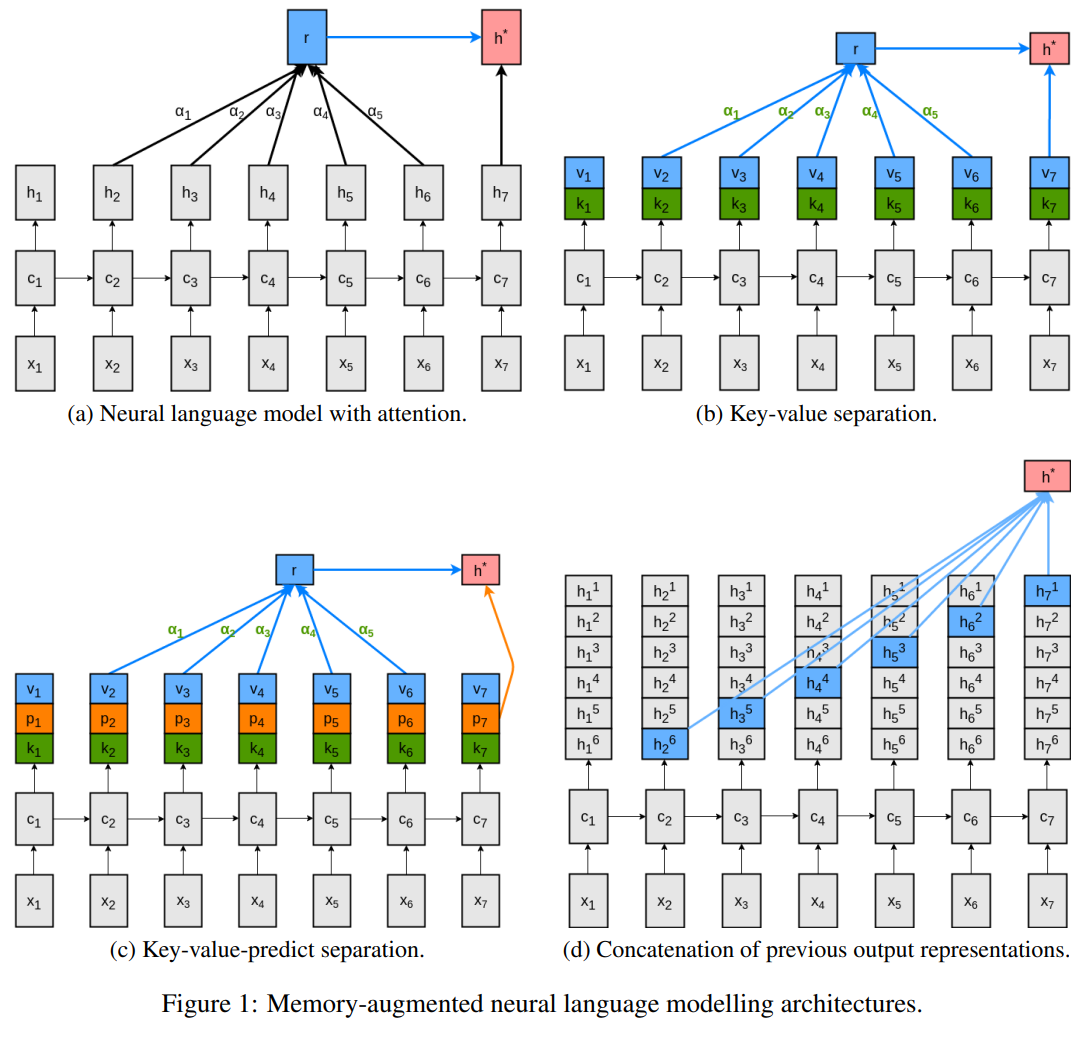

But there is a better way: Daniluk et al. (2017), frustrated by the short attention spans they were finding (Frustratingly Short Attention Spans in Neural Language Modeling) analzyed that the hidden states are oversubscribed in the sense that they have multiple roles to fulfill.

Neural language models predict the next token using a latent representation of the immediate token history. Recently, various methods for augmenting neural language models with an attention mechanism over a differentiable memory have been proposed. For predicting the next token, these models query information from a memory of the recent history which can facilitate learning mid- and long-range dependencies. However, conventional attention mechanisms used in memory-augmented neural language models produce a single output vector per time step. This vector is used both for predicting the next token as well as for the key and value of a differentiable memory of a token history.

They

- encode the distribution for predicting the next token

- serve as a key to compute the attention vector

- encode relevant content to inform future predictions

and are therefore open to breaking down into roles, directly inside the hidden states. The central idea is to separate the hidden vector into a Key part \(\boldsymbol{k}\) and a value part \(\boldsymbol{v}\), both size \(d\).

\[\mathbf{h}_t = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{k}_t^\top \\ \mathbf{v}_t^\top \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{2d}\](I am following the notation in Hochreiter and Adler closely here: ) For the score at timestep \(t\), additive attention is applied to the keys in a sliding window of size \(L\) up to the curren time step \(\boldsymbol{K}(t - 1) = \boldsymbol{k}(t - L), ..., \boldsymbol{k}(t - 1)\) and the current key \(\boldsymbol{k}(t)\).

\[\mathbf{e}_t = \mathbf{w}^\top \tanh(\mathbf{W}_K \mathbf{K} + [\mathbf{W}_k \mathbf{k}_t] \mathbf{1}^\top) \in \mathbb{R}^L\]\(\boldsymbol{W}_K\), \(\boldsymbol{W}_k \in \boldsymbol{R}^{dxd}\), \(\boldsymbol{w} \in \boldsymbol{R}^d\) and \(\boldsymbol{1} \in \boldsymbol{R}\).

Once again, the attention vector is obtained by applying softmax and the context vector is calculated by multiplying the attention vector by the values in \(\boldsymbol{V}(t - 1)\):

\[\boldsymbol{a}(t) = softmax(\boldsymbol{e}(t))\] \[\boldsymbol{c}(t) = \boldsymbol{V}(t - 1) \boldsymbol{a}(t)\]Daniluk et al. (2017) provide the following helpful schematic (top row):

We see the difference between previous attention mechanisms (a) and key-value attention (b). The context vector is denoted with r here.

Transformers

Transformer networks, or Transformers for short, are an easy thing in this blog post now, because the concepts have been introduced - I think this is the point the related lecture (and exercise at JKU) is making too.

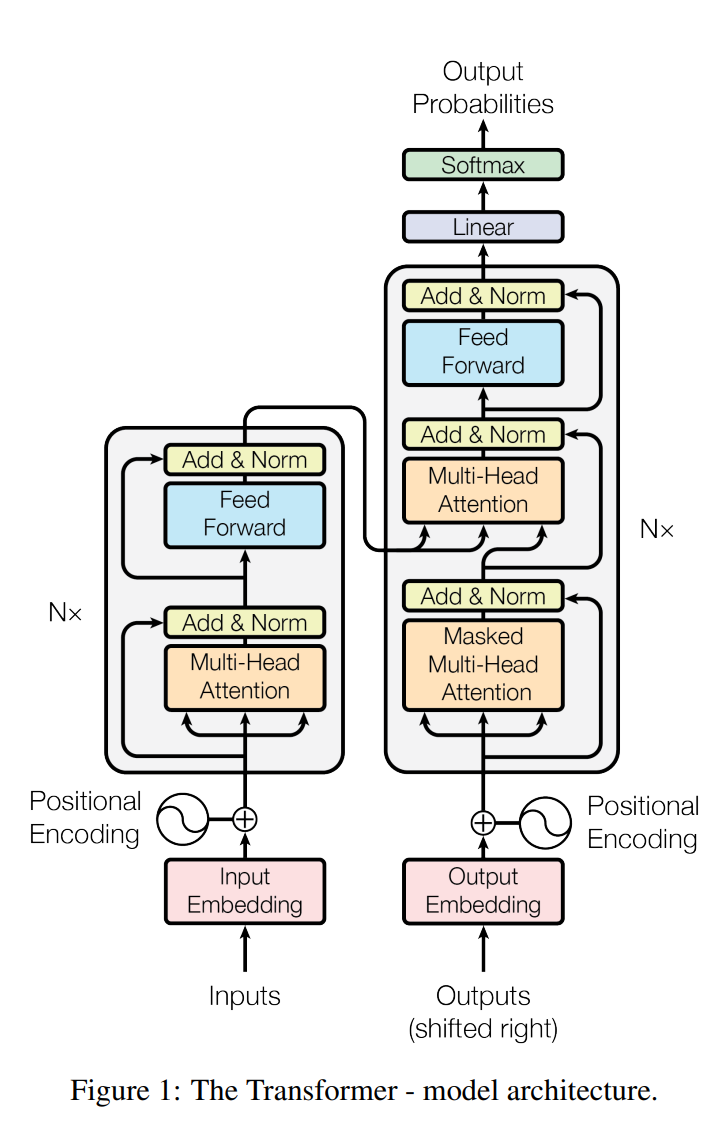

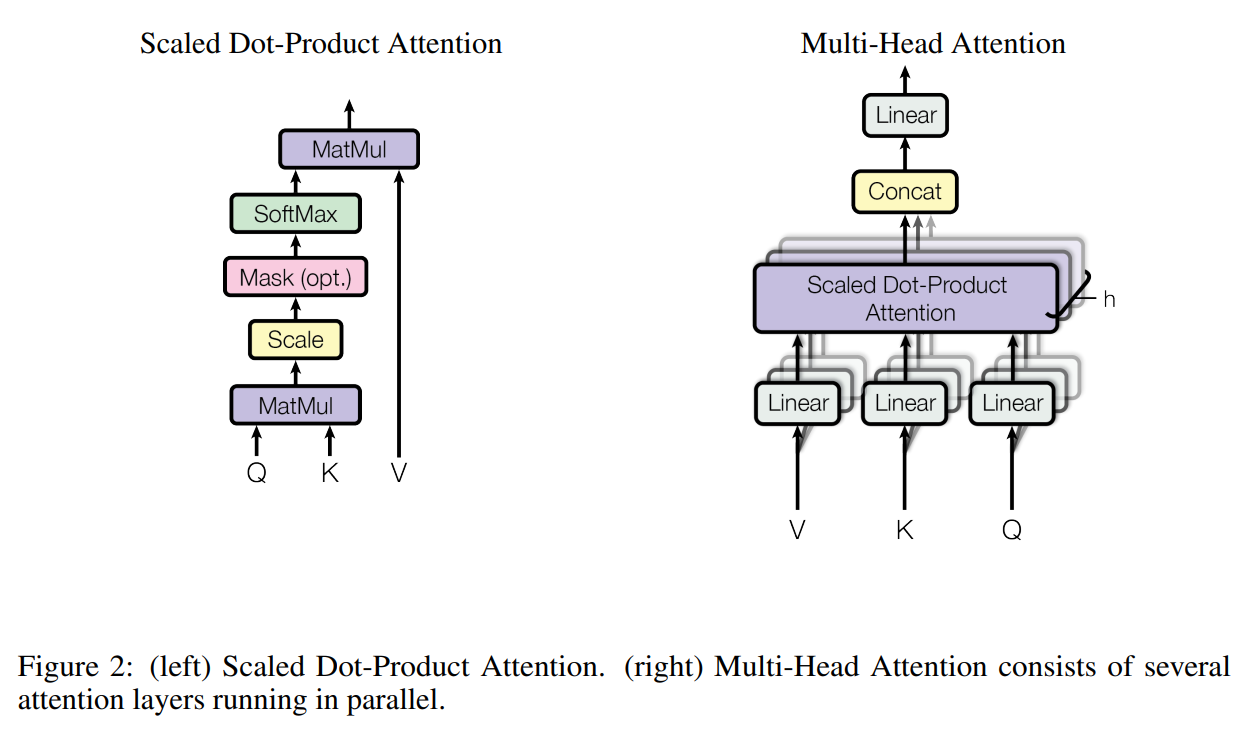

The NeurIPS 2017 publication Attention Is All you Need from Google Brain introduced the Transformer which is based on End-to-end Memory Network in Vaswani et al. (2017). It had great impact on the community. In contrast to previous attention models, the Transformer is not an RNN but a feedforward neural network. The Transformer relies on an extension of the key-value attention, it uses dot-product attention and it self-attending. It thus combines previously introduced concepts.

From the abstract from Attention Is All You Need:

The dominant sequence transduction models are based on complex recurrent or convolutional neural networks in an encoder-decoder configuration. The best performing models also connect the encoder and decoder through an attention mechanism. We propose a new simple network architecture, the Transformer, based solely on attention mechanisms, dispensing with recurrence and convolutions entirely. Experiments on two machine translation tasks show these models to be superior in quality while being more parallelizable and requiring significantly less time to train.

Going a bit deeper into the background in the 2017 paper for some of this stuff:

Self-attention, sometimes called intra-attention is an attention mechanism relating different positions of a single sequence in order to compute a representation of the sequence. Self-attention has been used successfully in a variety of tasks including reading comprehension, abstractive summarization, textual entailment and learning task-independent sentence representations […]. End-to-end memory networks are based on a recurrent attention mechanism instead of sequence aligned recurrence and have been shown to perform well on simple-language question answering and language modeling tasks […] To the best of our knowledge, however, the Transformer is the first transduction model relying entirely on self-attention to compute representations of its input and output without using sequence aligned RNNs or convolution.

End-to-end memory networks as in Sukhbaatar et al. 2015 might be a relevant concept to explore to understand where the thinking comes from fully. (Potential #future-blog-post)

Vaswani et al. go on to cite succesful BLEU scores in the abstract, which demonstrates the architecture's capacity. The most famous items from this paper are however the diagrams, I would say: First in overview.

Then in detail: where we a drawing out math operations as bubbles and lines basically, but yes, it works.

Encoder and decoder are enhanced by Multi-head attention, where the input is a matrix for emedded words representing. Positional encoding needs to be added since there is no sequential ordering inheren in the architecture of a feedforward network the way you have in RNN. So multi-head attention is applied to this, as in \(\boldsymbol{Z}_0 = \boldsymbol{X} + \boldsymbol{P} \in \boldsymbol{R}^{dxT}\) - here \(\boldsymbol{P}\) is said positional encoding.

The new thing is the Query, calculated on \(\boldsymbol{Z}_0\) with Key and Value as well. For the n-th Transformer unit (layer) the formulas read:

\[\mathbf{K}_n = \mathbf{W}_n^{K} \mathbf{Z}^{n-1}\] \[\mathbf{V}_n = \mathbf{W}_n^{V} \mathbf{Z}^{n-1}\] \[\mathbf{Q}_n = \mathbf{W}_n^{Q} \mathbf{Z}^{n-1}\]Now the overall idea, mathematically:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V\]But we can break this down some, highlighting \(\boldsymbol{E}_n\) as the score inside the main brackets, \(\boldsymbol{A}_n\) as the softmax of the score, and \(\boldsymbol{C}_n\) as context, the multiplication of \(\boldsymbol{A}_n\) with \(\boldsymbol{V}_n\).

There is a normalization of the score happening here, to prevent the softmax from saturation. This describes one attention head: Suppose we have \(h\) heads, together they produce \(h\) context matrices \(\boldsymbol{C}^1_n, ..., \boldsymbol{C}^h_n\).

The output of the multi-head attention unit follows:

\[\boldsymbol{R}_n = concat(\boldsymbol{C}^1_n, ..., \boldsymbol{C}^h_n) \boldsymbol{W}_n^Z \in \boldsymbol{R}^{dxT}\]The module also has shortcut connections, therefore the output is really:

\[\boldsymbol{R}_n = \boldsymbol{R}_n + \boldsymbol{Z}_{n-1}\]This is normalized via layer normalization and fed into a fully connected feedfoward network. The resulting output is then passed to a new multi-head attention in the decoder. The decoder is similar to the encoder but has two multi-head attention units.

The first attention unit only receives input from the previous decoder units and masks out subsequent positions of the input. The second attention unit also takes the output of the according encoding unit. In general, for a given sentence to translate, the model needs to encode the sentence once and then runs the decoder until a token arrives that indicates the end of the sequence.

(Hochreiter and Adler)

Transformers in Wolfram Language (WL)

I almost forgot! Of course, you can deploy Transformers in WL and load models like GPT and BERT super quickly too.

In fact, this is a great tool to take apart the models and learn about them that way, after you load and run them.

For the Mathematica Notebook input…

NetTake[bert, "embedding"]

… the front-end is:

![NetTake[bert, "embedding"] in Mathematica Notebook](/pages/image-44.png)

The transformer architecture then processes the vectors using 12 structurally identical self-attention blocks stacked in a chain. The key part of these blocks is the attention module, constituted of 12 parallel self-attention transformations, a.k.a. "attention heads".

Here is the difference between BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers - Devlin et al., 2018) and GPT (Generative Pre-Trained Tranformer, introduced by OpenAI, e.g. in their uber successful Language Models are Few-Shot Learners*) via the Mathematica Notebook interface. Both models are based on the Transformer architecture

GTP has a similar architecture as BERT. Its main difference is that it uses a causal self-attention, instead of a plain self-attention architecture. This can be seen by the use of the "Causal" mask in the AttentionLayer.

(Also in WL documentation/example)

ChatGPT is conversational AI system that leverages the power of Transformer models. It is designed to generate human-like responses in conversation-based settings, providing users with a seamless and interactive experience and has had a massive cultural impact, globally. (When did AI systems become cultural events? Maybe at this point.)

So, in WL:

NetExtract[bert, {"encoder", 1, 1, "attention", 1, "attention"}]

![NetExtract[bert, {"encoder", 1, 1, "attention", 1, "attention"}] in Mathematica Notebook](/pages/image-45.png)

NetExtract[gpt, {"decoder", 1, 1, "attention", 1, "attention"}]

![NetExtract[gpt, {"decoder", 1, 1, "attention", 1, "attention"}]](/pages/image-46.png)

Leaving the tool-question at this for the moment, I'll say that looking at these kinds of models' architecture will form a signficant component in my Masters Thesis (and Practical Component), write-up coming up soon (once I have the execution).

Update (Wolfram Summer Research Program 2024): Thank you, Nicolò, for letting me link this paper version of tracing a similar trajectory, but further, to Mamba, from a sequence learning deep dive talk at WSRP2024!

Reinforcement Learning Goes Deep (Part I): Q-learning Algorithm Implementation for a Grid World Environment

Repository on GitHub: for this Part I to a look at Deep Learning for Reinforcement Learning (RL), i.e. Deep Reinforcement Learning, I want to review some RL basics, largely following the well-tested Sutton and Barto text, ending on a note about planning vs learning and a focus on the foundational Bellman equation.

Excited to have been part of the uBern Winter School on Reinforcement Learning this February, to catch up on some basics.

Test Project: Environment, Policy, and the OpenAI Gym

The provided code is an implementation of the Q-learning algorithm in the OpenAI Gym tailored for a specific grid world environment. This environment includes an agent, an enemy, and a target, all located within a grid. The goal of the Q-learning algorithm is to learn an optimal policy for the agent to navigate the grid to reach the target while avoiding the enemy.

Key Components of the Code

- Initialization and Episode Loop: The run_episode_gwenv function initializes the episode by resetting the environment, which provides the initial state. The episode then runs for a maximum number of steps defined by _maxsteps, simulating the agent's interactions within the environment.

- State Representation: States are represented by the grid positions of the agent, enemy, and target. This requires a multidimensional Q-table to accommodate the multi-entity state space.

- Epsilon-Greedy Policy: During training, an epsilon-greedy policy is employed for action selection. This involves choosing a random action with a probability of epsilon (exploration) and the best-known action with a probability of 1 - epsilon (exploitation).

- Q-Table Update: The Q-value for the taken action is updated using the observed reward and the maximum Q-value of the next state, adjusted by the learning rate lr and discounted by the factor discount. This update mechanism is guided by the Bellman equation.

- Parameters:

- lr/alpha: Learning rate, controlling the Q-value update magnitude. (In the group at uBern my group focused on varying this parameter, hence the multiple versions at the end of Control.ipynb)

- discount/gamma: Discount factor, influencing the weight of future rewards.

- epsilon: Exploration-exploitation trade-off parameter.

- Optimal Policy Execution: If the optimal flag is true, the algorithm solely relies on exploitation by selecting the action with the highest Q-value for the current state, bypassing exploration.

- Return Values: Returns the updated Q-table and the reward from the final step of the episode, facilitating the evaluation of the learned policy.

Q-learning Algorithm for Grid World Environment

This Python function implements the Q-learning algorithm for a grid world environment where an agent navigates to reach a target while avoiding an enemy. It demonstrates key reinforcement learning concepts such as state representation, action selection, and Q-value updates.

def run_episode_gwenv(env, Q, lr, discount, epsilon=0.1, render=False, _maxsteps=20, optimal=False):

observation, _ = env.reset()

done = False

nsteps = 0

for x in range(_maxsteps):

nsteps += 1

if done:

break

if render:

env.render()

curr_state = observation

ax = curr_state['agent'][0]

ay = curr_state['agent'][1]

ex = curr_state['enemy'][0]

ey = curr_state['enemy'][1]

tx = curr_state['target'][0]

ty = curr_state['target'][1]

if not optimal:

randnum = np.random.rand(1)

if randnum < epsilon:

action = env.action_space.sample()

else:

action = np.argmax(Q[ax, ay, ex, ey, tx, ty,:])

observation, reward, done, _, info = env.step(action)

ax_next = observation['agent'][0]

ay_next = observation['agent'][1]

ex_next = observation['enemy'][0]

ey_next = observation['enemy'][1]

tx_next = observation['target'][0]

ty_next = observation['target'][1]

Q[ax, ay, ex, ey, tx, ty, action] += lr * \

(reward + discount * np.max(Q[ax_next, ay_next, ex_next, ey_next, tx_next, ty_next, :]) - Q[ax, ay, ex, ey, tx, ty, action])

else:

action = np.argmax(Q[ax, ay, ex, ey, tx, ty,:])

observation, reward, done, _, info = env.step(action)

return Q, reward

The implementation assumes the environment provides specific functionalities:

env.reset(): Resets the environment to an initial state.env.render(): Renders the current state of the environment.env.action_space.sample(): Samples a random action from the action space.env.step(action): Executes an action in the environment, returning the new state, reward, and other information.

Q-learning is a model-free reinforcement learning algorithm that aims to learn the value of an action in a particular state without requiring a model of the environment. It does so by estimating Q-values, which represent the expected utility of taking a given action in a given state and following the optimal policy thereafter.

The key features of Q-learning include:

- Model-free: It does not require knowledge of the environment's dynamics (i.e., the transition probabilities and rewards). This makes Q-learning highly versatile and applicable to a wide range of problems where the environment is unknown or difficult to model accurately.

- Off-policy: Q-learning learns the optimal policy independently of the agent's actions. This means it can learn from exploratory actions and even from observing other agents.

- Q-value Updates: The core of the algorithm involves updating the Q-values using the Bellman equation as an iterative update rule. This update minimizes the difference between the left-hand side (the current Q-value estimate) and the right-hand side (the observed reward plus the discounted maximum future Q-value).

Planning vs Learning

Planning, in the context of reinforcement learning, involves generating or improving a policy for decision-making by using a model of the environment. Unlike Q-learning, planning requires a model that predicts the outcomes of actions (transitions and rewards). Planning can be used to simulate experiences and improve policies without direct interaction with the environment. Key aspects of planning include:

- Model-based: Planning requires a model of the environment to predict the outcomes of actions. This model can be learned from experience or provided a priori.

- Simulated Experience: Planning algorithms use the model to simulate experiences, which are then used to improve the policy. This process can significantly reduce the need for actual interactions with the environment, which might be costly or dangerous.

- Value Iteration and Policy Iteration: Common planning algorithms include value iteration and policy iteration, both of which rely on the Bellman equation to iteratively improve value estimates or policies.

The Bellman Equation

The Bellman equation is central to both Q-learning and planning, serving as the mathematical foundation that describes the relationship between the value of a state (or state-action pair) and the values of its successor states. In its essence, the Bellman equation provides a recursive decomposition of value functions:

Bellman Equation for Value Functions:

\[V(s) = \max_a \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s' \mid s, a) V(s') \right]\]In Python code with a description of the parameters above as well:

def update_value_function(V, R, P, gamma, states, actions):

"""

Update the value function for each state using the Bellman equation.

Parameters:

- V: dict, value function, where keys are states and values are values of states

- R: function, reward function R(s, a) returning immediate reward

- P: function, transition probabilities P(s'|s, a) returning dict of {state: probability}

- gamma: float, discount factor

- states: list, all possible states

- actions: list, all possible actions

Returns:

- Updated value function V

"""

V_updated = V.copy()

for s in states:

V_updated[s] = max([R(s, a) + gamma * sum(P(s, a)[s_prime] * V[s_prime] for s_prime in states) for a in actions])

return V_updated

Bellman Equation for Q-Values

\[Q(s, a) = R(s, a) + \gamma \sum_{s'} P(s' \mid s, a) \max_{a'} Q(s', a')\]In Python code, with the parameters again:

def update_q_values(Q, R, P, gamma, states, actions):

"""

Update the Q-values for each state-action pair using the Bellman equation.

Parameters:

- Q: dict, Q-values, where keys are (state, action) pairs and values are Q-values

- R: function, reward function R(s, a) returning immediate reward

- P: function, transition probabilities P(s'|s, a) returning dict of {state: probability}

- gamma: float, discount factor

- states: list, all possible states

- actions: list, all possible actions

Returns:

- Updated Q-values Q

"""

Q_updated = Q.copy()

for s in states:

for a in actions:

Q_updated[(s, a)] = R(s, a) + gamma * sum(P(s, a)[s_prime] * max(Q[(s_prime, a_prime)] for a_prime in actions) for s_prime in states)

return Q_updated

These equations are at the heart of many reinforcement learning algorithms, providing a recursive relationship that is used to iteratively update the values or Q-values towards their optimal values.

Connecting to Planning Symbolic AI

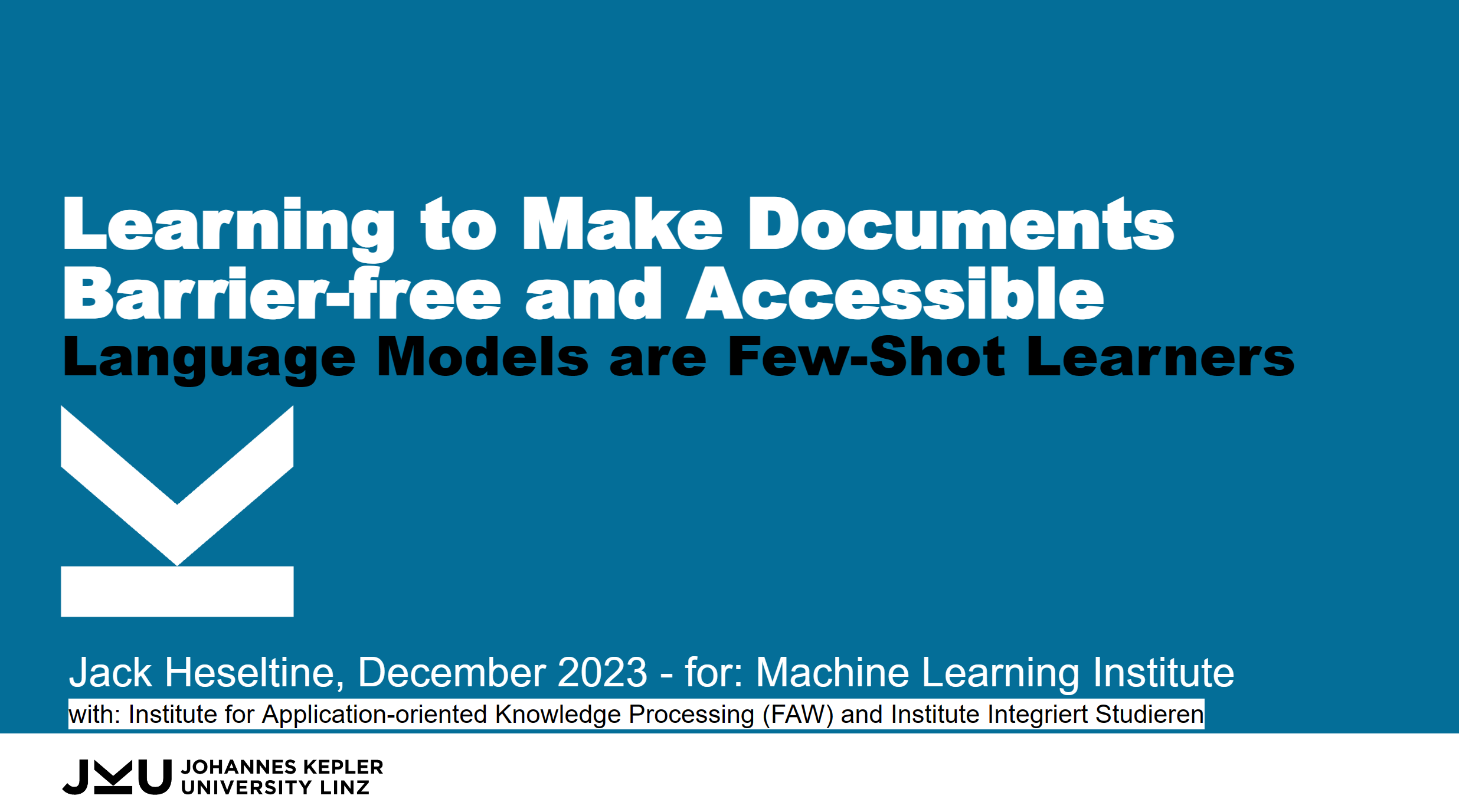

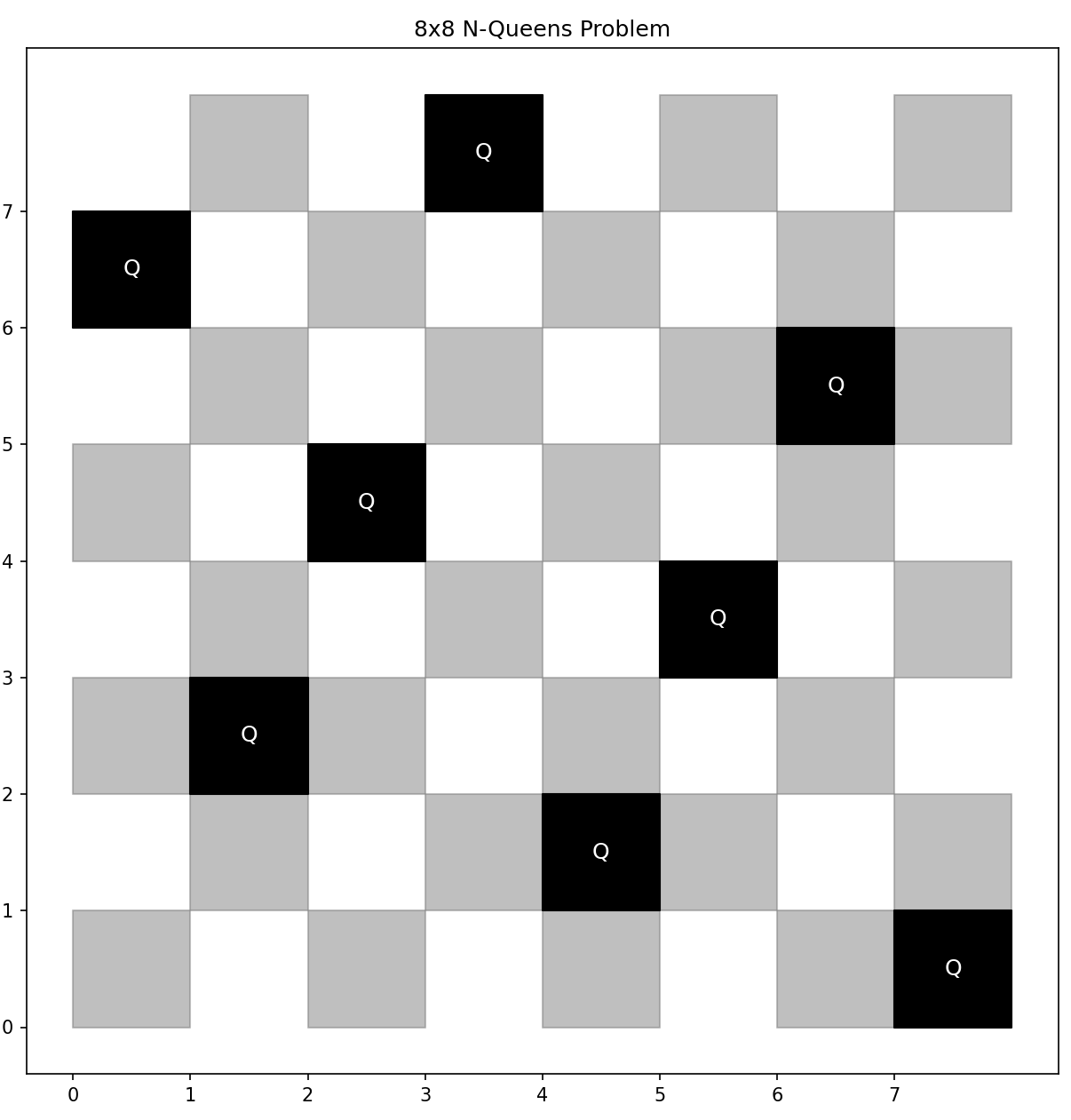

We already discussed planning vs learning, and now I would like to connect to Planning in Symbolic AI. See also my SMT Project in Planning (N-Queens Problem).

Planning in symbolic artificial intelligence, including techniques such as Satisfiability Modulation Theories (SMT), offers a different approach compared to the statistical or model-free methods seen in Q-learning. SMT, an extension of Boolean satisfiability (SAT), involves finding solutions to logical formulas over one or more theories (e.g., arithmetic, bit-vectors, arrays). These capabilities make SMT particularly well-suited for planning in deterministic, discrete environments where problems can be expressed as logical constraints. A classic example of such a problem is the N Queens puzzle, which can be solved using SMT by formulating it as a set of constraints.

Advantages and Considerations

- Deterministic Solutions: SMT provides a deterministic way to solve the N Queens problem, giving a definitive answer about the existence of a solution and providing the solution if it exists.

- Scalability: While SMT solvers are powerful, the complexity of solving such problems can grow exponentially with the size of N, making it challenging for very large N.

- General Applicability: The approach used for the N Queens problem can be adapted to solve a wide range of other constraint-based problems in various domains, including scheduling, configuration problems, and more.

In contrast to the statistical learning approaches in reinforcement learning, SMT and other symbolic AI planning methods offer precise, logic-based solutions to well-defined problems. This makes them particularly useful in scenarios where the problem space is discrete and can be fully expressed through logical constraints.

Connecting to Deep Learning

Next up: Part II, combining Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning for Deep Reinforcement Learning. (Coming soon.)

The deep learning idea experimentally explored in AdvancedRL.ipynb revolves around using a neural network as a function approximator for the Q-learning algorithm, a method known as Deep Q-Learning (DQN).

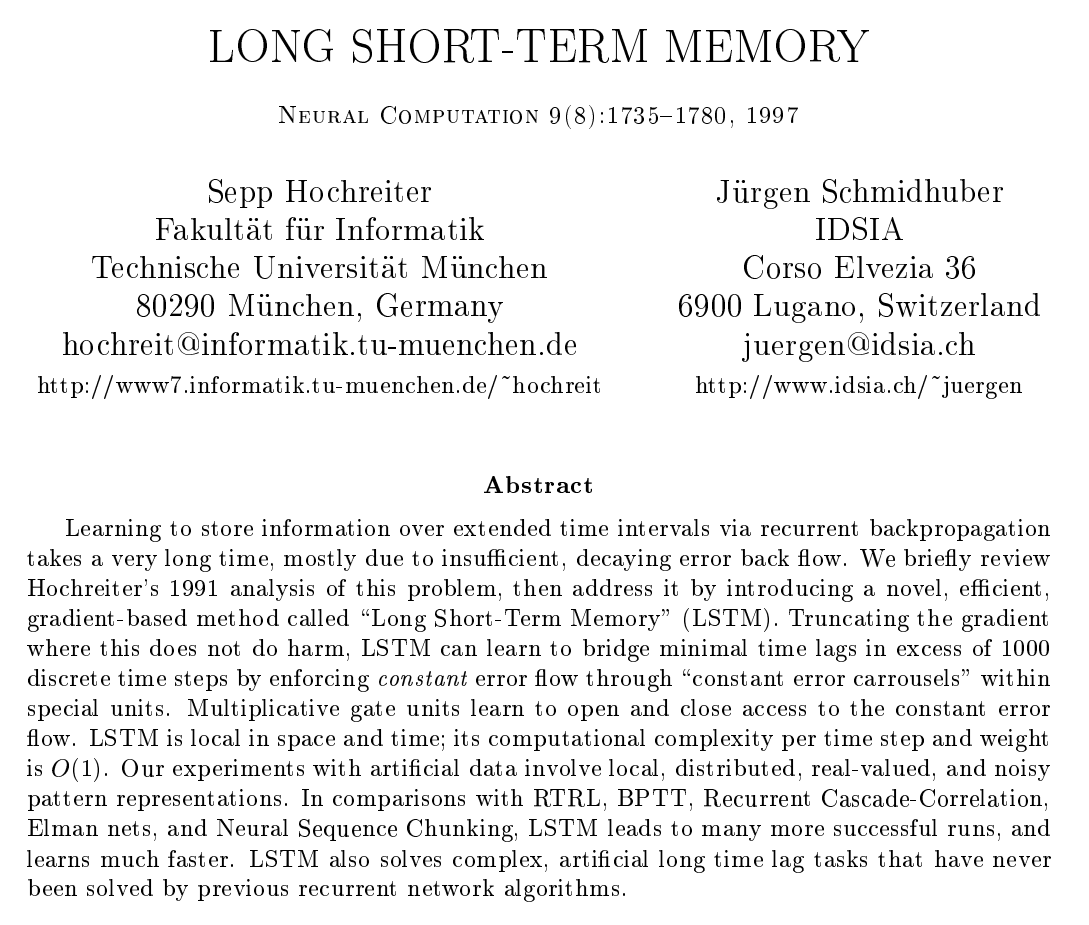

LSTM in the Linz AI Curriculum

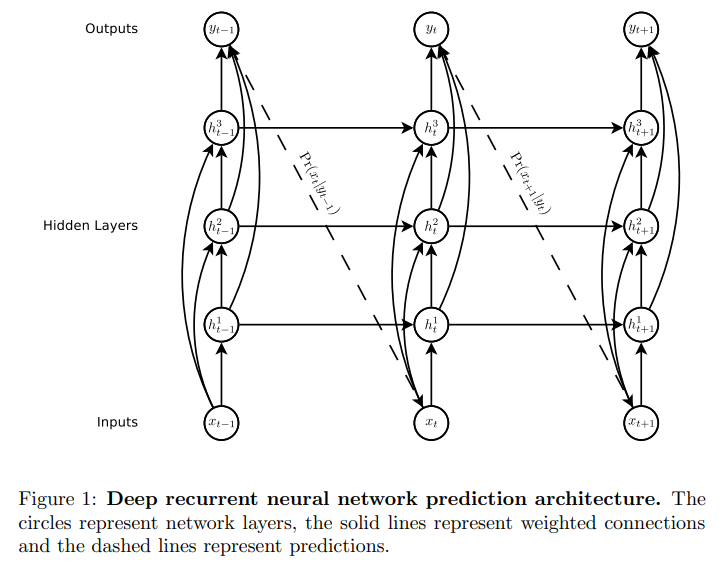

It's a core course for the Master's, treating a core AI datastructure so to speak, maybe as central as Convolutional Neural Networks, and at least framing the perspective on Transformers (where there is no separate course). After all, JKU's Sepp Hochreiter invented LSTM (Long-Short-Term Memory), but to go there, you need to start from RNNs (Recurrent Neural Networks) first.

This chain-like nature reveals that recurrent neural networks are intimately related to sequences and lists. They’re the natural architecture of neural network to use for such data.

RNN-Feats? Read The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks by Andrej Karpathy, maybe not so unreasonable in light of the quote from Chris Olah.

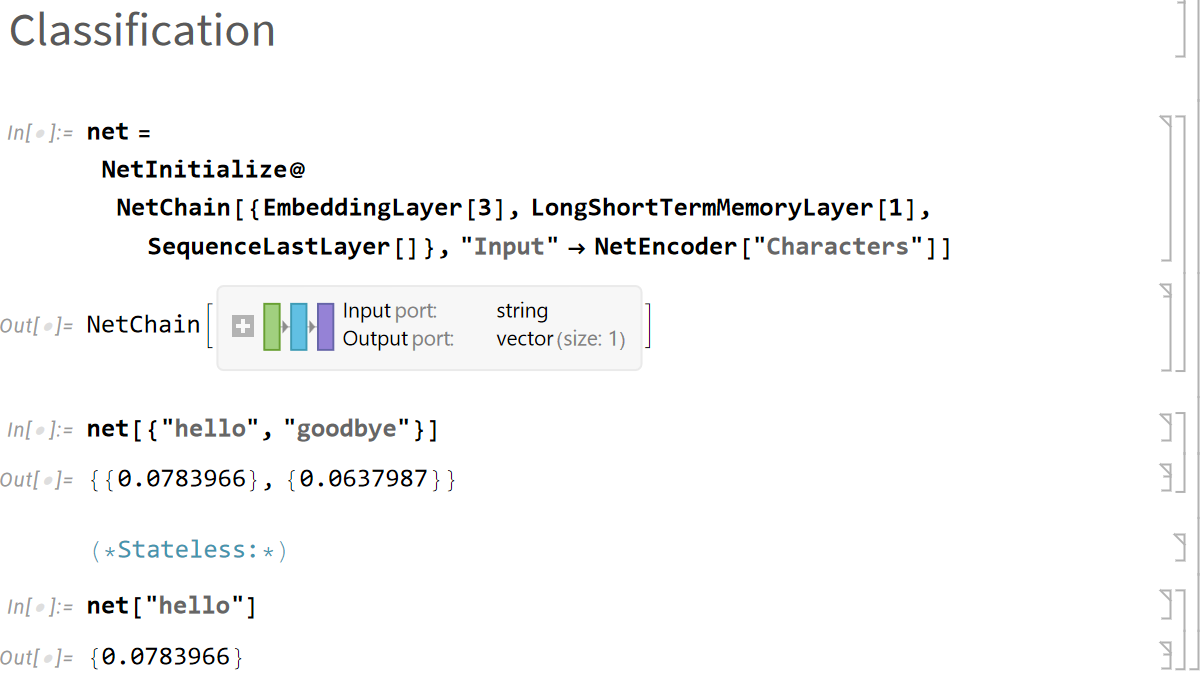

Quick Test: Wolfram Language LSTM Handling

Let's try something to begin, though, before jumping into more background on RNNs generally, and LSTM specifically, right up to the 2024 xLSTM Story (DE-world currently).

I know Python is the default in many AI curricula nowadays, but tools like Wolfram Language (WL) can be more effective because they are more high level. It really depends on what you want to emphasize: are you interested in implementation details, or do you just want to work with the networks?

Let's try this Input:

(*recurrent layer acting on variable-length sequences of 2-vectors*)

lstm = NetInitialize@

LongShortTermMemoryLayer[2, "Input" -> {"Varying", 2}]

(*Evaluate the layer on a batch of variable-length sequencesEvaluate the layer on a batch of variable-length sequences*)

seq1 = \{\{0.1, 0.4\}, \{-0.2, 0.7\}\};

seq2 = \{\{0.2, -0.3\}, \{0.1, 0.8\}, \{-1.3, -0.6\}\};

result = lstm[{seq1, seq2}]

Output:

\{\{\{-0.0620258, 0.0420743\}, \{-0.0738596,

0.0826808\}\}, \{\{0.0240281, -0.00213933\}, \{-0.0691157,

0.0852326\}, \{0.190297, -0.117645\}\}\}

For something just a bit more complicated, let's produce a number for each sequence: this is what it would look like to chain up the layers in WL.

Input:

net = NetInitialize@

NetChain[{EmbeddingLayer[3], LongShortTermMemoryLayer[1],

SequenceLastLayer[]}, "Input" -> NetEncoder["Characters"]]

Output after the jump, in a repo I made for the demo notebook. If you don't want to download the notebook and boot up Mathematica, the output looks like this, however.

What follows is a small taxonomy of RNNs, centering on LSTM, with the formulas!

RNN Architectures

Jordan

For the Jordan network, which is a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) that connects the output to the input of the network for the next time step, the equations are slightly different from those of LSTM-like networks we will look at in a moment.